Prions have a notorious reputation. They cause neurodegenerative disease, namely mad cow/Creutzfeld-Jakob disease. And the way these protein particles propagate – getting other proteins to join the pile – can seem insidious.

Yet prion formation could represent a protective response to stress, research from Emory University School of Medicine and Georgia Tech suggests.

A yeast protein called Lsb2, which can trigger prion formation by other proteins, actually forms a “metastable” prion itself in response to elevated temperatures, the scientists report.

The results were published this week in Cell Reports.

Higher temperatures cause proteins to unfold; this is a major stress for yeast cells as well as animal cells, and triggers a “heat shock” response. Prion formation could be an attempt by cells to impose order upon an otherwise chaotic jumble of misfolded proteins, the scientists propose.

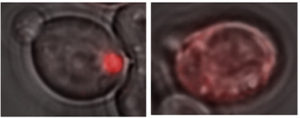

A glowing red clump can be detected in yeast cells containing a Lsb2 prion (left), because Lsb2 is hooked up to a red fluorescent protein. In other cells lacking prion activity (right), the Lsb2 fusion protein is diffuse.

“What we found suggests that Lsb2 could be the regulator of a broader prion-forming response to stress,” says Keith Wilkinson, PhD, professor of biochemistry at Emory University School of Medicine.

The scientists call the Lsb2 prion metastable because it is maintained in a fraction of cells after they return to normal conditions but is lost in other cells. Lsb2 is a short-lived, unstable protein, and mutations that keep it around longer increase the stability of the prions.

The Cell Reports paper was the result of collaboration between Wilkinson, Emory colleague Tatiana Chernova, PhD, assistant professor of biochemistry, and the laboratory of Yury Chernoff, PhD in Georgia Tech’s School of Biological Sciences.

“It’s fascinating that stress treatment may trigger a cascade of prion-like changes, and that the molecular memory of that stress can persist for a number of cell generations in a prion-like form,” Chernoff says.”Our further work is going to check if other proteins can respond to environmental stresses in a manner similar to Lsb2.” Read more