A mutation found in most melanomas rewires cancer cells’ metabolism, making them dependent on a ketogenesis enzyme, researchers at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University have discovered.

The V600E mutation in the gene B-raf is present in most melanomas, in some cases of colon and thyroid cancer, and in the hairy cell form of leukemia. Existing drugs such as vemurafenib target the V600E mutation — the finding points to potential alternatives or possible strategies for countering resistance. It may also explain why the V600E mutation in particular is so common in melanomas.

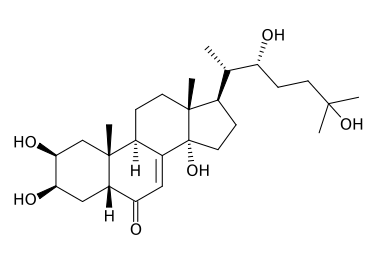

Researchers led by Jing Chen and Sumin Kang have found that by promoting ketogenesis, the V600E mutation stimulates production of a chemical, acetoacetate, which amplifies the mutation’s growth-promoting effects. (A feedback mechanism! Screech!)

The results were published Thursday, July 2 in Molecular Cell.