At some point, everyone has experienced a temporary groggy feeling after waking up called sleep inertia. Scientists know a lot about sleep inertia already, including how it impairs cognitive and motor abilities, and how it varies with the time of day and type of sleep that precedes it. They even have pictures of how the brain wakes up piece by piece.

People with idiopathic hypersomnia or IH display something that seems stronger, termed “sleep drunkenness,” which can last for hours. Czech neurologist Bedrich Roth, the first to identify IH as something separate from other sleep disorders, proposed sleep drunkenness as IH’s defining characteristic.

Note: Emory readers may recall the young Atlanta lawyer treated for IH by David Rye, Kathy Parker and colleagues several years ago. Our post today is part of IH Awareness Week® 2017.

Sleep drunkenness is what makes IH distinctive in comparison to narcolepsy, especially narcolepsy with cataplexy, whose sufferers tend to fall asleep quickly. Those with full body cataplexy can collapse on the floor in response to emotions such as surprise or amusement. In contrast, people with IH tend not to doze off so suddenly, but they do identify with the statement “Waking up is the hardest thing I do all day.”

At Emory, neurologist Lynn Marie Trotti and colleagues are in the middle of a brain imaging study looking at sleep drunkenness.

“We want to find out if sleep drunkenness in IH is the same as what happens to healthy people with sleep inertia and is more pronounced, or whether it’s something different,” Trotti says.

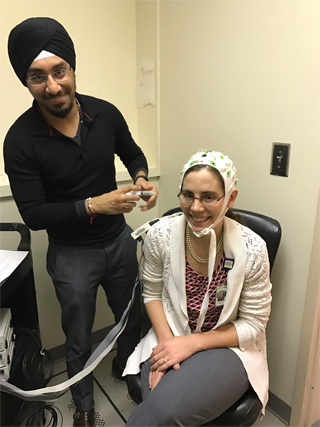

Principal investigator Lynn Marie Trotti, with senior research associate Prabhjyot Saini, preparing for a test run earlier this year. Photo courtesy of Diana Kimmel.

Few brain imaging studies have examined people with IH. One was reported by Canadian researchers at the 2017 Sleep Research Society meeting, but the abstract (large PDF – page A240) does not discuss functional imaging: how much different areas of the brain become activated during particular tasks.

Update: the Canadian paper was published in the journal Sleep.

Trotti has designed her study so that it captures the fuzzy state just after someone wakes up. Study participants are asked to take a nap, but don’t fall asleep IN the MRI. They go to sleep and wake up in a designated nap room nearby and are wheeled into the scanner.

Once awake, participants are given a test of working memory called “N-back”, in which they are supposed to pick repeated numbers out of several that appear one at a time. Afterwards, they can relax and are not given any test. For comparison, they also come in and perform the same memory test on another day without taking a nap first.

Trotti says she wants to examine something called the “default mode network” or DMN, regions of the brain that are active when someone isn’t paying attention to anything specific. The default mode network is sometimes connected with daydreaming.

Being asked to recall numbers will tend to pull someone’s brain out of the DMN, while 10 minutes left alone will let people get back to it. Trotti says she will be looking at how activity among the various parts of the DMN rise and fall together, as they are presumably talking to each other (a neuroscience concept called “functional connectivity”).

The study calls for three groups of people, 15 each: those with IH, narcolepsy with cataplexy and healthy controls. For people with IH or narcolepsy, imaging requires them to go off whatever wake-promoting medication they are on, although some participants may be asked to come back while taking medication.

One of the study participants, who asked not to be identified, reported that this requirement presented some challenges:

I was NOT supposed to fall asleep inside the scanner, which really worried me. The only reason I was able to stay awake for that long was because I had to do something, and then I made up songs to the noises that the machine was making. It was extremely difficult, but I did manage to stay awake.

Trotti has supervised clinical studies of the antibiotic clarithromycin and the benzodiazepine antidote flumazenil for sleepiness connected with IH. She is the chair of the medical advisory board for the Hypersomnia Foundation. The imaging study is funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.