On Thursday and Friday, Emory researchers participated in an online NIAID workshop about “post-acute sequelae” of COVID-19, which includes people with long COVID.

Long COVID has some similarities to post-viral ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/ chronic fatigue syndrome), which has a history of being dismissed or minimized by mainstream medicine. In contrast, the workshop reflected how seriously NIAID and researchers around the world are taking long COVID.

Post-acute is a confusing term, because it includes both people who were hospitalized with COVID-19, sometimes spending weeks on a ventilator or in an intensive care unit, as well as members of the long COVID group, who often were not hospitalized and did not seem to have a severe infection to begin with.

COVID-19 infection can leave behind lung or cardiac damage that could explain why someone would have fatigue and shortness of breath. But there are also signs that viral infection can perturb other systems of the body, leading to symptoms such as “brain fog” (cognitive/memory problems), persistent pain and/or loss of smell and taste.

Highlights from Thursday were appearances from patient advocates Hannah Davis and Chimere Smith, along with virologist Peter Piot, who all described their experiences. Davis is part of a patient-led long COVID-19 support group, which has pushed research forward.

One goal for the workshop was to have experts discuss how to design future studies, or how to take advantage of existing studies to gain insights. A major clue on what to look for comes from Emory immunologist Ignacio Sanz, who spoke at the conference.

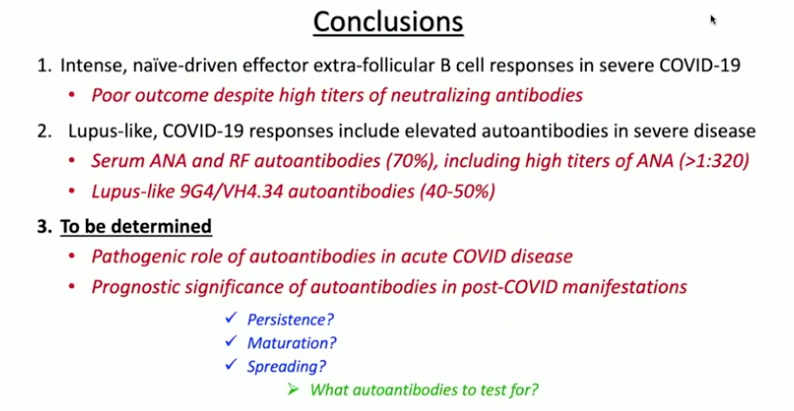

Sanz’s research has shown similarities between immune activation in people hospitalized at Emory with severe COVID-19 and in people with the autoimmune disease lupus. In lupus, the checks and balances constraining the immune system break down. A characteristic element of lupus are autoantibodies: antibodies that recognize parts of the body itself. Their presence in COVID-19 may be an explanation for the fatigue, joint pain and other persistent symptoms experienced by some people after their acute infections have passed.

For details on Sanz’s research, please see our write-up from October, their Nature Immunology paper, and first author Matthew Woodruff’s explainer. The Nature Immunology paper’s results didn’t include measurement of autoantibodies, but a more recent follow-up did (medRxiv preprint). More than half of the 52 COVID-19 patients tested positive for autoantibodies at levels comparable to those in lupus. In those with the highest amounts of the inflammatory marker CRP, the proportion was greater.

“It could be that severe viral illness routinely results in the production of autoantibodies with little consequence; this could just be the first time we’re seeing it,” Woodruff writes in a second explainer. “We also don’t know how long the autoantibodies last. Our data suggest that they are relatively stable over a few weeks. But, we need follow-up studies to understand if they are persisting routinely beyond infection recovery.”

Sanz’s group was looking at patients’ immune systems when both infection and inflammation were at their peaks. They don’t yet know whether autoantibodies persist for weeks or months after someone leaves the hospital. In addition, this result doesn’t say what is happening in the long COVID group, many of whom were not hospitalized.

Autoantibodies have also been detected in MIS-C (multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children), a rare complication that can come after an initial asymptomatic infection. In addition, some patients’ antiviral responses are impaired because of autoantibodies against interferons.

It makes sense that multiple mechanisms could explain post-COVID impairments, including persistent inflammation, damage to blood vessels or various organs, and blood clots/mini-strokes.

Anthony Komaroff from Harvard, who chaired a breakout group on neurology/psychiatry, said the consensus was that so far, direct evidence of viral infection in the brain is thin. Komaroff said that neuro/psych effects are more likely to come from the immune response to the virus.

There were breakout groups for different areas of investigation, such as cardiovascular, and gastrointestinal. Emory Vaccine Center director Rafi Ahmed co-chaired a session for immunologists and rheumatologists, together with Fred Hutch’s Julie McElrath.

Emory’s Carlos del Rio, who recently summarized long COVID for JAMA, spoke about racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19’s impact and said he expected similar inequities to appear with long COVID.

Reports from the breakout groups Friday emphasized the need to design prospective studies, which would include people before they became sick and take baseline samples. Some suggestions came for taking advantage of samples from the placebo groups in recent COVID-19 vaccine studies.

La Jolla immunologist Shane Crotty said that researchers need to track the relationship between infection severity/duration and post-infection impairments. “There’s a big gap on the virological side,” Crotty said. He noted that one recent preprint shows that SARS-CoV-2 virus is detectable in the intestines in some study participants 3 months after onset.