Pharmacologist Thomas Kukar is exploring a strategy to subtly redirect the enzyme that produces beta-amyloid, which makes up the plaques appearing in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients.

Thomas Kukar, PhD

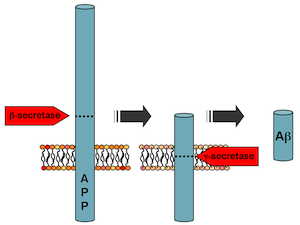

Preventing beta-amyloid production could be an ideal way to head off Alzheimer’s, but the reason why a subtle approach is necessary was illustrated last year by disappointing results from a phase III clinical trial. The experimental drug semagacestat was designed to block the enzyme gamma-secretase, which “chomps†on the amyloid precursor protein (APP), usually producing an innocuous fragment but sometimes producing toxic beta-amyloid.

Gamma-secretase also is involved in processing a bunch of other vital proteins, such as Notch, central to an important developmental signaling pathway. Scientists suspect that this is one of the reasons why trial participants who received semagacestat did worse on cognitive/daily function measures than controls and saw an increase in skin cancer, leading watchdogs to halt the study.

While a postdoc at Mayo Clinic Jacksonville and working with Todd Golde and Edward Koo, Kukar identified compounds – gamma-secretase modulators or GSM’s — that may offer an alternative.

“We are looking at a strategy that’s different from global gamma-secretase inhibition,†he says. “The approach is: don’t inhibit the enzyme overall, but instead modify its activity so that it makes less toxic products.â€

Gamma-secretase chomps on amyloid precursor protein, and how it does so determines whether toxic beta-amyloid is produced. It also processes several other proteins important for brain function.

This line of inquiry started when it was discovered that some anti-inflammatory drugs also could reduce beta-amyloid production. Then, the crosslinkable probes Kukar was using to identify which part of the gamma-secretase fish was doing the chomping ended up binding the bait (APP). This suggested that drugs might be able to change how the enzyme acts on one protein, APP, but not others.

Now an assistant professor at Emory, he is examining in greater detail how gamma-secretase modulators work. Two recent papers he co-authored in Journal of Biological Chemistry show 1) how the proteins that gamma-secretase chews up are “anchored†in the membrane and 2) how selective GSM’s can be on amyloid precursor protein.

Although clinical studies of a “first generation†GSM, tarenflurbil, were also stopped after negative results, Kukar says GSM’s still haven’t really been tested adequately, since researchers do not know if the drugs are really having an effect on beta-amyloid levels in the brain. Newer compounds coming through the pharmaceutical pipeline are more potent and more able to get into the brain. While looking for more potent GSM’s is critical, Kukar says it’s equally as important to understand how gamma-secretase works to understand its biology.