A recent Associated Press story highlighted clinical trials aimed at helping kidney transplant recipients give up their anti-rejection drugs:

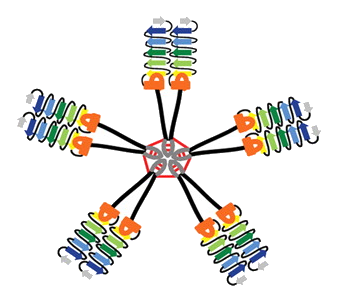

The experimental approach: Transplant the seeds of a new immune system along with a new kidney. It’s the 21st-century version of a bone marrow transplant, and possible for now only if the transplanted kidney comes from a living donor.

How does it work? Doctors cull immune system-producing stem cells and other immunity cells from the donor’s bloodstream. They blast transplant patients with radiation and medications to wipe out part of their own bone marrow, far more grueling than a regular kidney transplant. That makes room for the donated cells to squeeze in and take root, creating a sort of hybrid immunity that scientists call chimerism, borrowing a page from mythology.

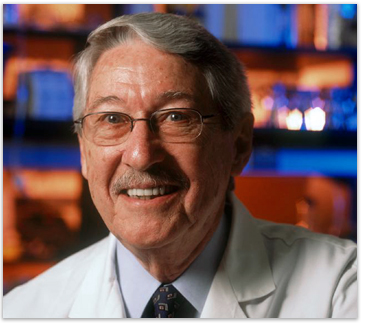

Emory Transplant Center scientific director Allan Kirk is leading a study that takes a similar approach, involving a depletion of the recipient’s immune cells and an infusion of bone marrow, which introduces new immune cells from the donor.

Allan Kirk, MD, PhD

Nature Medicine also has a good explanation of this area of research. Kirk is quoted in this recent story:

“The impetus to take the risk and pull people off immunosuppressants completely is lower now,†says Kirk… “It’s all about risk-benefit ratios and about making smart decisions with the tools we have—and we have a lot more tools now.â€

Why go through so much trouble to avoid anti-rejection drugs? The most common drugs taken by transplant recipients, called calcineurin inhibitors, can reduce an individual’s ability to fight infections, lead to high blood pressure and high blood sugar and, ironically, tend to damage the kidney over time. Emory scientists played a major role in developing an alternative, belatacept, which was approved last year by the FDA.

Emory transplant surgeon Ken Newell was also mentioned in the AP story for his study of rare individuals who were able to go “cold turkey” and avoid having their immune systems reject their donated kidneys. One of these individuals, Lisa Robinson, had an interesting story to tell about how came to that point:

Three years after her kidney transplant, she found it hard to tolerate the side effects of the immunosuppressive drugs, which included swelling, weight gain and depression. On top of that, her creatinine levels were rising, indicating that her donated kidney was losing function. Without explicit approval from her doctor, she decided to taper off her drugs, first cyclosporine and then steroids.

“This turned out to be the right choice for me, but I’m not suggesting that others do what I did,” she says. “Everyone has to figure out what works for them. My main motivation was that I didn’t want to go through another kidney transplant.”

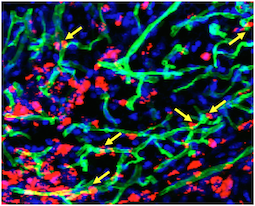

Based on data from Robinson and other people who had similar experiences, Newell has been able to identify a pattern of genes turned on in their immune cells that may predict whether someone could be able to become “tolerant.” Much of transplant biology focuses on one type of immune cell (T cells), but Newell found that the cells that may make the biggest difference for long-term tolerance are different, B cells. This makes sense because of B cells’ role in chronic rejection, Emory’s Stuart Knechtle has written.

Posted on

March 29, 2012 by

Quinn Eastman

in Uncategorized