A new antibiotic compound can clear infection of multi-drug resistant gonorrhea in mice with a single oral dose, according to a new study led by researchers at Penn State and Emory.

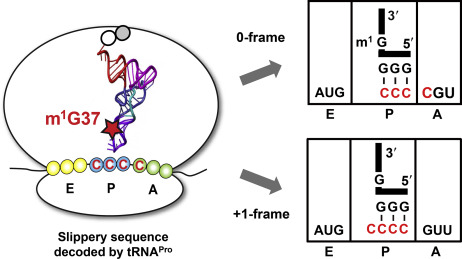

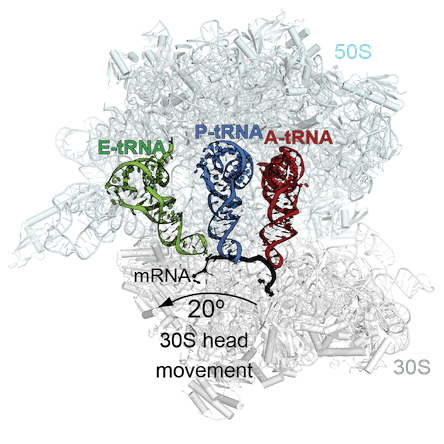

Like other antibiotics, this one targets the ribosome, the factories that generate proteins in bacterial (and human) cells. But it does so at a site that is different from other antibiotics. This one interferes with the process of trans-translation, which bacteria use to rescue their ribosomes out of rough spots.

The results were published in Nature Communications. This was a collaboration involving several groups: biochemist Christine Dunham’s at Emory and Ken Keiler’s at Penn State, along with others at Florida State, the Uniformed Services University and the Massachusetts-based pharmaceutical company Microbiotix.

Zachary Aron, director of chemistry at Microbiotix, is the first author of the paper, and the compound is called MBX-4132. It is also active against other Gram-positive bacteria, including tuberculosis and Staph aureus, and the company says it will continue to optimize it.

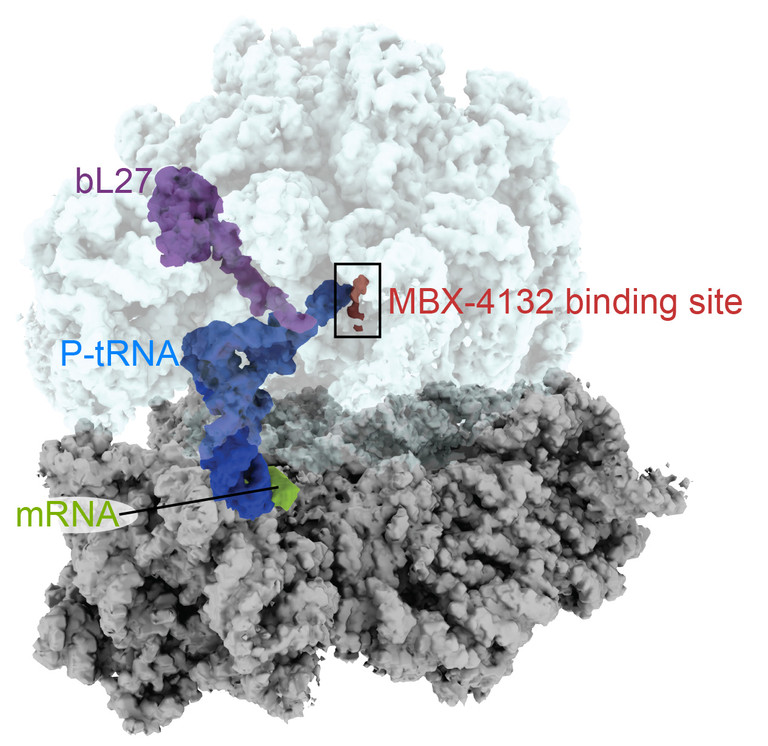

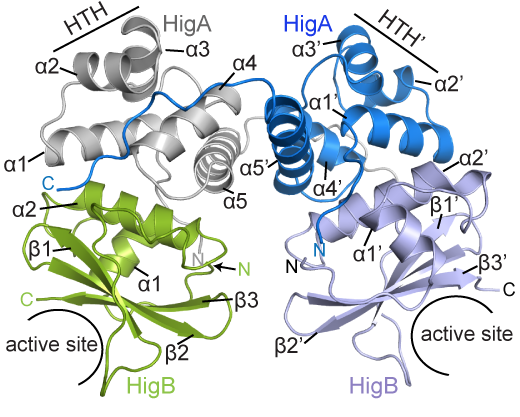

At Emory, Dunham’s lab used cryo-electron microscopy to produce high-resolution images of the compound as it binds to the bacterial ribosome — see below.

“A derivative of MBX-4132 binds to a location on the ribosome that is different from all known antibiotic binding sites,” Dunham says. “The new drug also displaces a region of a ribosomal protein that we think could be important during the normal process of trans-translation. Because trans-translation only occurs in bacteria and not in humans, we hope that the likelihood of the compound affecting protein synthesis in humans is greatly reduced, a hypothesis strongly supported by the safety and selectivity studies performed by Microbiotix.”

Multi-drug resistant gonorrhea is listed by the CDC as one of the five most urgent threats, among antibiotic resistant bacteria. Half of all gonorrhea infections are resistant to at least one antibiotic.