Emory neurosurgeon Jon Willie and colleagues recently published a paper on deep brain stimulation in a mouse model of narcolepsy with cataplexy. Nobody has ever tried treating narcolepsy in humans with deep brain stimulation (DBS), and the approach is still at the “proof of concept” stage, Willie says.

People with the “classic” type 1 form of narcolepsy have persistent daytime sleepiness and disrupted nighttime sleep, along with cataplexy (a loss of muscle tone in response to emotions), sleep paralysis and vivid dream-hallucinations that bleed into waking time. If untreated, narcolepsy can profoundly interfere with someone’s life. However, the symptoms can often be effectively, if incompletely, managed with medications. That’s why one question has to be: would DBS, implemented through brain surgery, be appropriate?

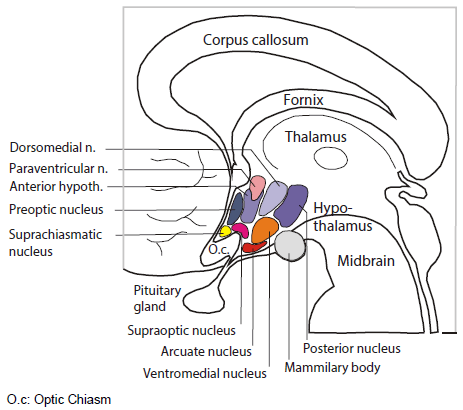

The room where it happens. Sandwiched between the thalamus and the pituitary, the hypothalamus is home to several distinct bundles of neurons that regulate appetite, heart rate, blood pressure and sweating, as well as sleep and wake. It’s as if in your house or apartment, the thermostat, alarm clock and fuse box were next to each other.

Emory audiences may be familiar with DBS as a treatment for conditions such as depression or Parkinson’s disease, because of the pioneering roles played by investigators such as Helen Mayberg and Mahlon DeLong. Depression and Parkinson’s can also often be treated with medication – but the effectiveness can wane, and DBS is reserved for the most severe cases. For difficult cases of narcolepsy, investigators have been willing to consider brain tissue transplants or immunotherapies in an effort to mitigate or interrupt neurological damage, and similar cost-benefit-risk analyses would have to take place for DBS.

Willie’s paper is also remarkable because it reflects how much is now known about how narcolepsy develops. Read more