When a patient is fighting a brain tumor, pathologists usually obtain a tiny bit of the tumor, either through a biopsy or after surgery, and prepare a microscope slide. Looking at the slide, they can sometimes (but not always) tell what type of tumor it is. That allows them to have an answer, however tentative, for that critical question from the patient: “How long have do I have?” as well as give guidance on what kind of treatment will be best.

Dan Brat, a pathologist specializing in brain tumors at Emory Winship Cancer Institute, gave a presentation this week explaining how he has been asking more complicated questions, ones only a network of pathologists armed with sophisticated computers can answer:

- What genes tend to be turned on or off in the various types of brain tumors?

- What does the pattern look like when a tumor is running out of oxygen?

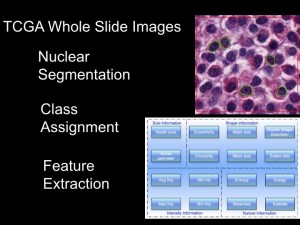

- What if we get a “robot pathologist” to look at hundreds of thousands of brain tumor slides?

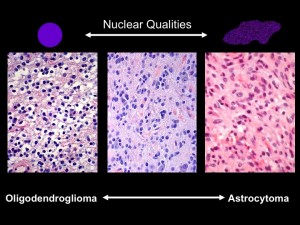

Under the microscope, the shapes of cell nuclei in brain tumors look different depending on the type of tumor.

Brat was speaking at a caBIG (cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid) conference, taking place at the Emory Conference Center this week. caBIG is a computer network sponsored by the National Cancer Institute that allows doctors to share experimental data on cancers. Brat explained that low-grade brain tumors come in two varieties: oligodendrogliomas and astrocytomas. Under the microscope, cell nuclei in the first tend to look round and smooth, but the second look elongated and rough. Kind of like the differences between an orange and a potato, he said. He and colleague Jun Kong designed a computer program that could tell one from the other. They had the program look through almost 400,000 slides, using resources compiled through caBIG (Rembrandt and Cancer Genome Atlas databases). Sifting through the data, they could find that certain genes are turned on in each kind of tumor.

Imagine a "robot pathologist" that can sift through thousands of images from brain tumor samples. |

Daniel Brat, MD, PhD, principal investigator for the In Silico Brain Tumor Research Center |

Eventually, this kind of information could help a patient with a brain tumor get good responses to those “How long?” and “How am I going to get through this?” questions.

Joel Saltz, who leads Emory’s Center for Comprehensive Informatics, has been a central figure in developing tools for centers such as Emory’s In Silico Brain Tumor Research Center. In September 2009, Emory was selected to host one of five “In Silico Research Centers of Excellence” by the National Cancer Institute.