Scientists have devised a triple-stage ‘cluster bomb’ system for delivering the chemotherapy drug cisplatin, via tiny nanoparticles designed to break up when they reach a tumor.

Details of the particles’ design and their potency against cancer in mice are described this week in PNAS Early Edition. They have not been tested in humans, although similar ways of packaging cisplatin have been in clinical trials.

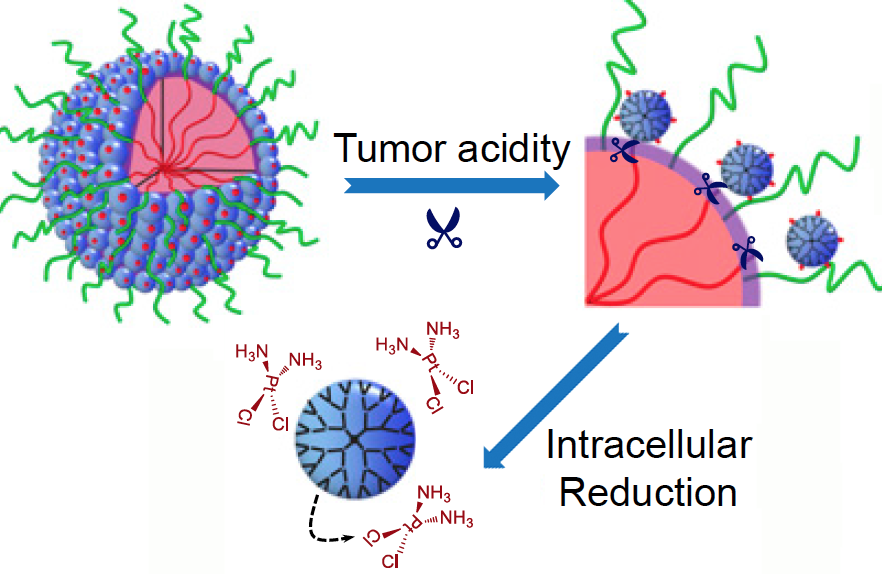

What makes these particles distinctive is that they start out relatively large — 100 nanometers wide — to enable smooth transport into the tumor through leaky blood vessels. Then, in acidic conditions found close to tumors, the particles discharge “bomblets” just 5 nanometers in size.

Inside tumor cells, a second chemical step activates the platinum-based cisplatin, which kills by crosslinking and damaging DNA. Doctors have used cisplatin to fight several types of cancer for decades, but toxic side effects — to the kidneys, nerves and inner ear — can limit its effectiveness.

The PNAS paper is the result of a collaboration between a team led by professor Jun Wang, PhD at the University of Science and Technology of China, and researchers led by professor Shuming Nie, PhD in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory. Nie is a member of the Discovery and Developmental Therapeutics research program at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. The lead authors are graduate student Hong-Jun Li and postdoctoral fellows Jinzhi Du, PhD and Xiao-Jiao Du, PhD.

“The negative side effects of cisplatin are a long-standing limitation for conventional chemotherapy,” says Jinzhi Du. “In our study, the delivery system was able to improve tumor penetration to reach more cancer cells, as well as release the drugs specifically inside cancer cells through their size-transition property.”

The researchers showed that their nanoparticles could enhance cisplatin drug accumulation in tumor tissues. When mice bearing human pancreatic tumors were given the same doses of free cisplatin or cisplatin clothed in pH-sensitive nanoparticles, the level of platinum in tumor tissues was seven times higher with the nanoparticles. This suggests the possibility that nanoparticle delivery could restrain the toxic side effects of cisplatin during cancer treatment. Read more

_files/140827-Photo-KE.jpg)