Biomarkers circulating in the bloodstream may serve as a predictive window for recurrent stroke risk and also help doctors accurately assess what is happening in the brains of patients with acute traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Researchers at Emory University School of Medicine, led by principal investigator Michael Frankel, MD, Emory professor of neurology and director of Grady Memorial Hospital’s Marcus Stroke & Neuroscience Center, are studying biomarkers as part of two ancillary studies of blood samples using two grants from the National Institutes of Health.

In the $1.47 million, four-year grant called “Biomarkers of Ischemic Outcomes in Intracranial Stenosis†(BIOSIS), Emory researchers are analyzing blood samples from 451 patients from around the country who were enrolled in a study known as SAMMPRIS (Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent stroke in Intracranial Stenosis), the first randomized, multicenter clinical trial designed to test whether stenting intracranial arteries would prevent recurrent stroke.

Researchers in the SAMMPRIS study recently published their results in the New England Journal of Medicine, showing that medical management was more effective than stenting in preventing recurrent strokes in these patients. Frankel’s BIOSIS research team is using blood samples from these same patients to continue learning more about the molecular biology of stroke to predict risk of a stroke occurring in the future.

“Our goal is to learn more about stroke by studying proteins and cells in the blood that reflect the severity of disease in arteries that leads to stroke. If we can test blood samples for proteins and cells that put patients at high risk for stroke, we can better tailor treatment for those patients,†says Frankel.

Patients with narrowed brain arteries, known as intracranial stenosis, have a particularly high risk of disease leading to stroke. At least one in four of the 795,000 Americans who have a stroke each year will have another stroke within their lifetime. Within five years of a first stroke, the risk for another stroke can increase more than 40 percent. Recurrent strokes often have a higher rate of death and disability because parts of the brain already injured by the original stroke may not be as resilient.

The other study, “Biomarkers of Injury and Outcome in ProTECT III†(BIO-ProTECT)” is a $2.6 million, five-year NIH grant in which Frankel’s team will use blood to determine what is happening in the brain of patients with acute TBI. The blood samples are from patients enrolled in the multicenter clinical trial ProTECT III (Progesterone for Traumatic brain injury, Experimental Clinical Treatment), led by Emory Emergency Medicine Professor, David Wright, MD, to assesses the use of progesterone to treat TBI in 1,140 patients at 17 centers nationwide.

In the BIO-ProTECT study, Emory is collaborating with the Medical University of South Carolina, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Michigan and Banyan Biomarkers.

TBI is the leading cause of death and disability among young adults in the US and worldwide. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 1.4 million Americans sustain a traumatic brain injury each year, leading to 275,000 hospitalizations, 80,000 disabilities, and 52,000 deaths.

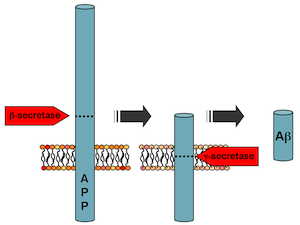

Acute TBI leads to a cascade of cellular events set in motion by the initial injury that ultimately lead to cerebral edema (swelling of the brain), cellular disruption and sometimes death. Tissue breakdown leads to the release of proteins into the bloodstream. These proteins may serve as useful biomarkers of the severity of the injury and perhaps provide useful information about response to treatment.

Using the large patient group in the ProTECT III trial, the researchers hope to validate promising TBI biomarkers as predictors of clinical outcome and also evaluate the relationship between progesterone treatment, biomarker levels and outcome.

“If we can better determine the amount of brain injury with blood samples, we can use blood to help doctors better assess prognosis for recovery, and, hopefully whether a patient will respond to treatment with progesterone,†says Frankel.