In ancient Greek mythology, the souls of the dead were made to drink from the river Lethe, so that they would forget their past lives. Something analogous happens to genes at the very beginning of life. Right after fertilization, the embryo instructs them to forget what it was like in the egg or sperm where they had come from.

This is part of the “maternal-to-zygote transition”: much of the epigenetic information carried on and around the DNA is wiped clean, so that the embryo can start from a clean slate.

Developmental biologist Lewis Wolpert once said: “It is not birth, marriage or death which is

the most important time in your life, but gastrulation,” referring to when the early embryo separates into layers of cells that eventually make up all the organs. Well, the MZT, which occurs first, comes pretty close in importance.

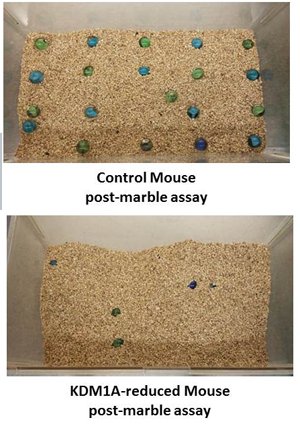

When this process of epigenetic reprogramming is disrupted, the consequences are often lethal. Emory cell biologists David Katz and Jadiel Wasson discovered that when mouse eggs are missing an enzyme that is critical for the MZT, on the rare instances when the mice survive to adulthood, they display odd repetitive behaviors. The mice are really strong on marble burying, an assay used to gauge obsessive-compulsive-like behavior (photos provided by Jadiel Wasson).

“Our results demonstrate how defects in reprogramming may influence the development of altered behaviors, or even complex psychiatric disorders,” Katz says. Their findings were published recently in eLife.

Update: a paper on this topic was also published in the same journal by Edith Heard and colleagues.

While these mice were created by genetic engineering techniques, the effects may simulate other disruptions of the post-fertilization reprogramming process. Those disruptions might come from genetic changes or environmental influences on oocytes such as hormones or parental age, he says. More here (full press release).

The enzyme that Wasson and Katz found was so critical for reprogramming is KDM1A/LSD1, a demethylase that removes epigenetic markers from histones, the spool-like proteins that package DNA.

Emory’s Xiaodong Cheng was part of a 2007 Nature paper showing mechanistically how histone methylation is tightly connected to DNA methylation. A recent paper on that point from Cambridge, UK is here.