![queen_bee_04~s600x600[1]](http://www.emoryhealthsciblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/queen_bee_04s600x6001-150x150.jpg) Every time scientists identify genetic risk factors for a human disease or a personality trait, it seems like more weight accumulates on the “nature” side of the grand balance between nature and nurture.

Every time scientists identify genetic risk factors for a human disease or a personality trait, it seems like more weight accumulates on the “nature” side of the grand balance between nature and nurture.

That’s why it’s important to remember how much prenatal and childhood experiences such as education, nutrition, environmental exposures and stress influence later development.

At the Emory/Georgia Tech Predictive Health Symposium in December, biologist Victor Corces outlined this concept using a particularly evocative example: bees. A queen bee and a worker bee share the same DNA, so the only thing that determines whether an insect will become the next queen is whether she consumes royal jelly.

As Corces explains, good or bad upbringing (including royal jelly) doesn’t change the sequence of the DNA, but it does change how DNA is packaged inside cells. The packaging on a stretch of DNA determines whether its genetic information will get read or stay bundled up. The study of these influences is called epigenetics, literally “above genetics.”

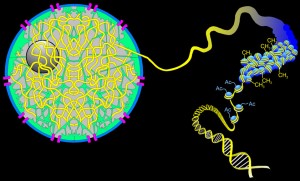

Blue spheres depict histones, while Ac stands for acetylation, a chemical modification of histones that tends to loosen their grip on DNA. Methylation appears as CH3 on the DNA itself.

Cells can modulate DNA packaging with enzymes that attach or remove chemical modifications on the histones, the spool-like proteins that DNA wraps around in the nucleus. Cells can even give DNA something resembling a censor’s stamp — methylation — specifying genes that shouldn’t be read.

The list of all the modifications gets complicated quickly. Histones can also get methylation, with effects depending on the exact spot.

Crystallographer Xiaodong Cheng, a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar at Emory, has been studying the histone-modifying enzymes. He and other scientists believe that a histone code connects DNA packaging to the cell’s decision on whether a gene should be on or off.