Editor’s note: This post was a collaboration with MMG graduate student Megan Hockman.

They were brought together by their children’s epilepsies, and by rapid advances in genetic sequencing. Only a few years ago, these families would have been isolated, left to deal with their children’s seizures and neurological problems on their own. Now, they’ve organized themselves and are shaping the future of research.

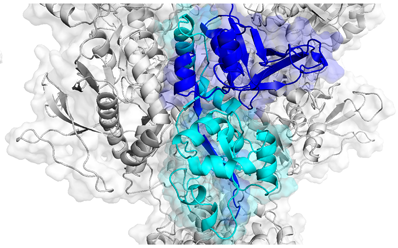

Agonist binding domains of NMDA receptors, where several disease-causing mutations can be found. Adapted from Swanger et al, AJHG (2016).

In mid-September, parents of children affected by variations in GRIN genes gathered at Emory Conference Center to meet with scientists to discuss current research. GRIN disorders occur because of mutations in genes encoding NMDA receptors, which play key roles in memory, learning and neuronal development. NMDA receptors are a type of receptor for glutamate, the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. The receptors themselves are encoded by multiple genes and assemble into tetramers. When their function is altered by mutations in one of these genes, symptoms appear in infancy or early childhood, usually including epilepsy and developmental delay.

The conference was the first time several patient advocacy groups oriented around GRIN-related disorders had met together, says Denise Rehner, president of the CureGRIN Foundation and mother of an affected child. For parents, this was an opportunity to connect with each other and advocacy groups, and to interact with scientists. For researchers, it was a chance to hear from those who are being impacted by their studies, and to discuss better ways to share data.

“We got a chance to explain to all the stakeholders – patient groups, foundations, companies – exactly what we do,” said Emory neuroscientist and conference organizer Stephen Traynelis, director of the Center for Functional Evaluation of Rare Variants. Traynelis and colleague Hongjie Yuan have been tracking the direct impacts of mutations on the function of the NMDA receptor. In doing so, they plan work with clinicians to compile registries, linking specific functional data to patient symptoms.

In addition to understanding underlying mechanisms and outcomes of GRIN disorders, researchers want to figure out how to treat affected children with existing drugs. Several options exist for targeting NMDA receptors, such as dextromethorphan (a cough suppressant) or memantine, approved for symptoms of Alzheimer’s. Traynelis and Yuan previously collaborated with the Undiagnosed Disease Program (now the Undiagnosed Disease Network) at the National Institutes of Health to investigate memantine as a treatment for a child with a GRIN2A mutation, showing that the drug could reduce seizure burden in one patient.

A more recent paper in Brain compiles similar work on GRIN2D mutations, concluding that a patient’s age is important in evaluating treatment response: “While in vitro assays of responsiveness to memantine and other such agents may be helpful in predicting whether a given patient may or may not respond, they are not sufficient to gauge the effects of timing of treatment.”

The mutations in GRIN genes are rarely shared between cases; over 400 variants have been discovered so far. While the memantine studies were a promising initial step, Traynelis hopes to make progress in evaluating therapies on a broader basis. “We want to capture both the positive and negative data – not just a drug that worked once for an exceptional case,” he said.

The individual nature of each case has made the compilation of data a challenge. Other researchers, such as Ingo Helbig at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, are attempting to find common links between symptoms and specific GRIN variants using pre-existing patient data. In this way, he hopes to get a better picture of “the GRIN landscape” and find what makes individual GRIN patients unique when compared to others.

In order to find solutions, researchers are using patient registries and “retrospective clinical trials”. Retrospective clinical trials utilize existing data to compare cases in which patients have taken treatments to those which have not. Instead of administering a single drug with unknown effects, researchers can look at the outcomes and the specific patient variant and determine viability of the treatment for other, similar cases. In this way, they can look at a wide range of antiepileptics and other therapies and choose which may work for individual cases. Yuan is also testing neurosteroids that may be useful in treating GRIN disorders.

On a second day of the conference, family groups such as Austin’s Purpose, the GRIN2B Foundation, the GRIN Disorders Research Foundation, and the CureGRIN Foundation met to discuss how to work together. (Denise Rehner from CureGRIN provided video.) Other neurodevelopmental disorder communities, such as those connected with Rett syndrome and Dravet syndrome, can provide models, participants said.

Parents discussed issues such as medical form fatigue, long term hope versus short term confusion, and “social media as an amplifier of emotion.” One woman tearfully asked: “How do you have time to do your research? How do you have time to start a foundation? I just feel like I’m not doing enough for my daughter!”

“For most of us, the science is pretty intense,” replied Liz Marfia-Ash, president of the GRIN2B Foundation. “Learn it at your level and that’s OK.” Goals for the network of parents and researchers will be to mitigate the intensity and make the science more accessible. The CureGRIN Foundation is currently organizing next year’s conference, which will be held in Boston.