Nothing he tried had worked. For Sigurjon Jakobsson, the trip to Atlanta with his family was a last-ditch effort to wake up. He had struggled with sleeping excessively for several years before coming from Iceland to see a visionary neurologist, who might have answers.

In high school, Sigurjon was a decathlete competing as part of Iceland’s national sports team. But at the age of 16, an increasing need for sleep began to encroach upon his life. Sigurjon needed several alarm clocks to get out of bed and was frequently late to school or his job at a construction company. He often slept more than 16 hours in a day.

Sigurjon feeling awake (Atlanta, summer 2018)

When Sigurjon describes his experiences, they sound like depression, although his mood and lack of motivation appear more a consequence of his insatiable desire to sleep. He quit sports. He dropped out of college and became isolated and lost touch with close friends.

“Your will to do things just kinda dies,” he says. “And then you’re always trying and trying again. It just gets worse. You kinda die inside from being tired all the time.”

At the recommendation of a neurologist in Iceland, Sigurjon’s family sought out David Rye, who is known internationally for his research on idiopathic hypersomnia, a poorly understood sleep disorder.

Sigurjon’s profile suggested that he might respond to an unconventional medication Rye has experience with: flumazenil. It was not originally developed for use with sleep disorders and is generally given intravenously. It is available — in oral lozenge form and in a cream applied to the skin — only through a few compounding pharmacies in the United States. That’s why Sigurjon had to come to Atlanta to try it.

After evaluating his medical history and symptoms, and giving him a series of tests, Rye concluded that Sigurjon has idiopathic hypersomnia.

“When you listen to him,” Rye says, “he sleeps too much, he has a hard time waking up, he takes long naps, he has ‘sleep drunkenness’…that’s hypersomnia.”

Redrawing the map

Over the last several years, Rye has been calling attention to the neglected status of idiopathic hypersomnia, or IH. Hypersomnia means “too much sleep,” but the word idiopathic can be confounding. It means the cause is not known.

David Rye, MD, PhD

Sleep scientists have argued about IH’s origin and mechanisms, and whether it’s one, two or many entities. Rye and his team have an idea for how to redraw the map.

“We’re trying to change sleep medicine here,” Rye says. “We want to at least get patients in through the right doorway so that we can direct them more swiftly to an accurate diagnosis and a tailored treatment.”

Sleep specialists are trained to recognize conditions that can render someone drowsy, with two of the most common being sleep apnea and narcolepsy. Sleep apnea comes from interruptions in breathing, which interfere with sleep’s restorative nature and put strain on the heart. Narcolepsy—one form of it, at least—is also well-understood: an autoimmune attack eliminates cells in the brain that keep someone awake and alert.

People with hypersomnia find that sleep is taking over their lives, hour by hour. In contrast, for people with narcolepsy, the boundary between sleep and wake is less stable.

Some people with persistent sleepiness don’t fit neatly into these categories. Understanding what lies behind their sleepiness could unlock new insights into how the brain works. It could also change the lives of people, such as Sigurjon, who have slipped through the cracks of modern medicine.

Rye compares hypersomnia and narcolepsy to apples and oranges. (He even created a T shirt design to drive home this point.) He has proposed that in some people with symptoms like Sigurjon’s, the circuits within the brain that promote and maintain sleep are overactive. This idea is supported by the Emory team’s use of flumazenil for IH and similar disorders.

Flumazenil is an antidote against benzodiazepines and related compounds, a class of anti-anxiety and sedative drugs. People undergoing an uncomfortable medical procedure, such as a colonoscopy, are often given one of them (midazolam/Versed) for “conscious sedation.” If they get too much and have trouble breathing, flumazenil can reverse the sedation. It can also be used to counteract overdoses of other benzodiazepines in the ER.

In 2007, Rye and his colleagues observed flumazenil’s effects with Anna Sumner Pieschel, an Atlanta attorney whose life was being overtaken by sleep. Anna had to take a leave from her job and couldn’t drive. She already had tried conventional medications, such as the “smart drug” modafinil, together with amphetamines. Anna found it difficult to tolerate the doses she needed to stay awake and experienced periodic crashes.

Rye has compared Anna’s treatment with stimulants to “driving a car with the parking brake on.” He and a colleague, nurse practitioner and sleep researcher Kathy Parker, suspected something else was going on. Laboratory tests indicated that her spinal fluid mimicked the biochemical effects of benzodiazepines, even though she wasn’t taking any. A more extensive account is in this 2013 Emory Medicine article.

Looking for alternatives for Anna, Rye and Parker obtained some flumazenil from manufacturer Hoffmann-La Roche, through a limited “compassionate use” arrangement. They figured out how to deliver it as under-the-tongue lozenges and a skin cream. Flumazenil—in combination with other medications—helped Anna return to work. She eventually became a partner at her firm, and felt confident enough to get married and start a family.

Nodding toward her energetic preschool-aged son, Anna says: “If you told me six years ago that this would be my life, I wouldn’t have thought it was possible… Today I have everything I never thought I would have.”

Anticipation of a different life

Sigurjon’s family, and some of the doctors he saw in Iceland, were unsure how to help him. He had already tried other medications that are often used to treat persistent sleepiness: modafinil and methylphenidate (Ritalin). They could physically keep him awake, but he still didn’t feel right.

“They did nothing but keep me from falling asleep when I was tired,” he says. “This is my last resort. If this doesn’t work, I don’t know.”

In July 2018, Sigurjon, then 23, got a chance to let a flumazenil lozenge dissolve under his tongue. As seen in the Georgia Public Broadcasting video, both his family and Anna were watching. The effect was not immediate.

First, Sigurjon mentioned feeling irritated or agitated in his legs: “My body is telling me to go move…to go running or go do something.” Within five minutes the drug’s effects began to kick in, in earnest, and a smile planted itself on his and his parents’ faces.

“It’s like my eyes are being lifted up and yeah—it’s a strange feeling,” he says. “It feels really good…I don’t even remember feeling like this.”

After all the anticipation, it was possible that part of what he was experiencing could be a placebo effect. The Emory researchers wanted to monitor changes in his alertness physiologically. Electrodes placed on Sigurjon’s face monitored his brain waves (EEGs). On the days he tried flumazenil, he performed a series of tests measuring his reaction time, which became faster for several hours after taking the drug. In addition, after applying a skin cream containing it, he was able to wake up spontaneously for the first time in years —to his surprise—without the aid of an alarm clock.

In January 2019, Sigurjon told Rye that he was slowly building stamina to be able to work at his construction job and thinking about going to school again. Rye has other patients from European countries who periodically visit Atlanta for a check-up and to maintain their flumazenil prescriptions.

Flumazenil is not magic, and its effects on healthy or sleep-deprived people have been inconsistent in previous studies. In a review of 153 Emory Sleep Center patients who didn’t respond well to conventional stimulants, about 60 percent reported that flumazenil helped them become more awake. A smaller number (39 percent) stuck with the drug long term; the effects weakened over time in a few patients. The most common adverse side effects were dizziness and anxiety. (This was not a randomized controlled clinical trial. Rather, it was a retrospective analysis of patients who had already been treated.)

Growth of a community

Sigurjon and Anna are part of a worldwide community of people with IH and related sleep disorders. Many people with IH have had to stop school, leave their jobs, or apply for disability. Some can’t drive or are cautious about driving long distances.

A nonprofit patient advocacy organization called the Hypersomnia Foundation is working to raise awareness and promote research. Rye is the chair of the foundation’s scientific advisory board, and his colleague, neurologist Lynn Marie Trotti, is chair of the medical advisory board.

“We’ve been seeing how for some people, IH really puts their life on hold, especially if the usual medications don’t work for them,” Trotti says.

To gather more information on how the disorder manifests in different people, the Hypersomnia Foundation, in cooperation with South Dakota-based Sanford Research, has created a patient registry. It has more than 1,400 participants so far.

“This registry has been really useful,” Trotti says, “because it allows us to document the actual profile of this disorder and to see patterns that we wouldn’t necessarily have seen in a smaller group of people.”

The Foundation organizes conferences on IH, maintains a directory of healthcare providers with experience treating IH and related disorders, and has recently implemented a research award program. It has also created guides for families and caregivers on educational accommodations and considerations for undergoing anesthesia.

Quickly: take a nap

Sigurjon was actually diagnosed in 2016 in Iceland with a form of narcolepsy: type 2, or narcolepsy without cataplexy. Cataplexy is a distinctive symptom, which is tightly associated with the type 1 autoimmune form of narcolepsy: muscle weakness triggered by emotions or stress.

People with narcolepsy who do not have cataplexy are usually diagnosed through something called the Multiple Sleep Latency Test. In this test, someone is asked to take four or five naps throughout the day. If they zonk out quickly enough, averaging a delay of less than 8 minutes, and enter REM sleep during two or more naps, then a narcolepsy diagnosis applies. If they fall asleep quickly, but don’t enter REM sleep, then idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) applies.

Rye and Trotti have shown that the sleep latency test works well for type 1 narcolepsy but provides inconsistent results for people with type 2 narcolepsy and IH. That is, the test can put someone in one of those last two categories, but if they take the test again, they will often get a different result. This happened to Sigurjon.

Overall, the finding supports Rye and Trotti’s call that the map of sleep disorders needs to be redrawn. Other sleep scientists have agreed that additional diagnostic criteria for IH, such as monitoring how many hours someone sleeps throughout the week, are valid. More discussion on how to revise the categories is underway. Under current criteria, the prevalence of IH is estimated to be around 1 in 3,000. (Other estimates vary.)

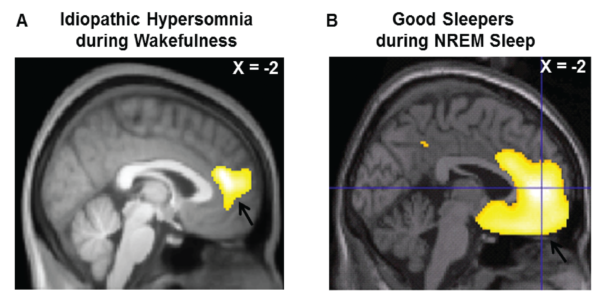

From Boucetta et al: Altered Regional Cerebral Blood Flow in Idiopathic Hypersomnia. Sleep (2017) Courtesy of Oxford University Press.

Pictures of the sleepy brain

Sleep researchers in Montreal have shown that the patterns of blood flow in the brain in people with IH are altered, when compared with healthy controls. Even while they are awake, the brains of people with IH look somewhat like those of healthy people who are sleeping.

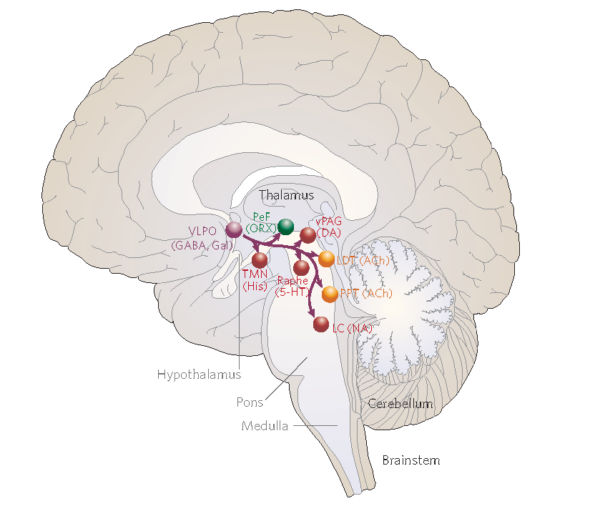

Rye thinks that in people with IH, circuits of the brain that promote sleep may be overactive. One area where this could be happening is the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) in the hypothalamus, a region of the brain that regulates sleep, appetite and body temperature. During the onset of sleep, the VLPO calms other circuits within the brain that would otherwise stimulate someone to be awake and alert. See below.

At Emory, Trotti is conducting a brain imaging study of people with IH and narcolepsy, looking at the transitions between wake and sleep.

Note on flumazenil

When Sigurjon tried flumazenil on camera, it was not part of a clinical trial. Although flumazenil is not FDA-approved for the treatment of sleep disorders, the FDA allows doctors to prescribe a drug for an unapproved use when they judge that it is medically appropriate for their patient. This is known as prescribing a drug “off label.”

Rye and Trotti prescribe flumazenil only to patients who have not responded adequately to more conventional wake-promoting medications, and after advising them about potential risks and side effects. It can be difficult to get insurance coverage for flumazenil, and out of pocket, it can cost hundreds of dollars per month.

In 2017, Emory obtained a patent for the use of flumazenil to treat hypersomnia and related sleep disorders, and the technology has been licensed to a company that is conducting clinical studies on a related drug for idiopathic hypersomnia.

The VLPO (ventrolateral preoptic area) is one of the regions of the brain that actively shuts down wake-promoting centers of the brain, using the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA. From Saper et al Nature (2005).

The mechanism of action of flumazenil is still under investigation.