Police procedural television shows, such as Law + Order, have introduced many to the Internal Affairs Bureau: police officers that investigate other police officers. This group of unloved cops comes to mind in connection with the HIV/AIDS research published this week by Rama Amara’s lab at Yerkes National Primate Research Center and Emory Vaccine Center.

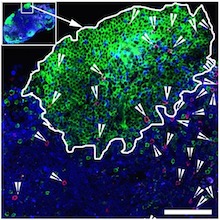

“Killer” antiviral T cells (red spots) can be found in germinal centers. The green areas are B cell follicles, which HIV researchers have identified as major reservoirs for the virus. Image courtesy of Rama Amara.

HIV infection is hard to get rid of for many reasons, but one is that the virus infects the cells in the immune system that act like police officers. The “helper” CD4 T cells that usually support immune responses become infected themselves. For the immune system to fight HIV effectively, the “killer” CD8 antiviral T cells would need to take on their own CD4 colleagues.

When someone is HIV-positive and is taking antiretroviral drugs, the virus is mostly suppressed but sticks around in a reservoir of inactive infected cells. Those cells hide out in germinal centers, specialized areas of lymph nodes, which most killer antiviral T cells don’t have access to. A 2015 Nature Medicine paper describes B cell follicles, which are part of germinal centers, as “sanctuaries” for persistent viral replication. (Imagine some elite police unit that has become corrupt, and uniformed cops can’t get into the places where the elite ones hang out. The analogy may be imperfect, but might help us visualize these cells.)

Amara’s lab has identified a group of antiviral T cells that do have the access code to germinal centers, a molecule called CXCR5. Knowing how to induce antiviral T cells displaying CXCR5 will be important for designing better therapeutic vaccines, as well as efforts to suppress HIV long-term, Amara says. The paper was published in PNAS this week.

This group of CXCR5-positive CD8 T cells has received a lot of convergent attention recently. Rafi Ahmed’s lab has reported analogous cells in mice with chronic viral infections, and his team showed that they are the ones that respond to PD-1-blocking cancer immunotherapy agents. In addition, a recent Science Translational Medicine paper found similar cells in HIV-infected humans, calling them “follicular CD8 T cells.”

One final thought — just because CD8 T cells have the access code to germinal centers doesn’t mean they will attack infected cells. Amara’s lab found they can be stimulated to do so outside the body, but how to do that so they “drain the reservoir”? Stay tuned.