Scientists at Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University have identified compounds that stop two elusive anticancer targets from working together. In addition to striking two birds with one stone, this research could expand the envelope of what is considered “druggable.”

Many of the proteins and genes that have critical roles in cancer cell growth and survival have been conventionally thought of as undruggable. That’s because they’re inside the cell and aren’t enzymes, for which chemists have well-developed sabotage strategies.

Many of the proteins and genes that have critical roles in cancer cell growth and survival have been conventionally thought of as undruggable. That’s because they’re inside the cell and aren’t enzymes, for which chemists have well-developed sabotage strategies.

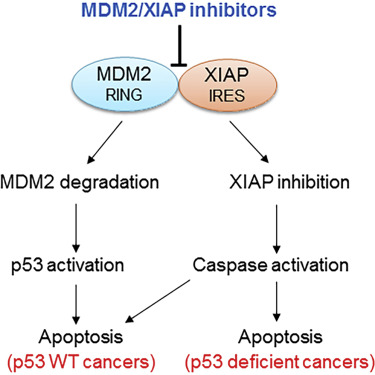

In a twist, the potential anticancer drugs described in Cancer Cell disable an interaction between a notorious cancer-driving protein, MDM2, and a RNA encoding a radiation-resistance factor, XIAP.

The compounds could be effective against several types of cancer, says senior author Muxiang Zhou, MD, professor of pediatrics (hematology/oncology) at Emory University School of Medicine and Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center.

In the paper, the compounds show activity against leukemia and neuroblastoma cells in culture and in mice, but a fraction of many other cancers, such as breast cancers (15 percent) and sarcoma (20 percent), show high levels of MDM2 and should be susceptible to them.

The co-first authors of the paper are assistant professor of pediatrics Lubing Gu, MD, research associate Hailong Zhang, PhD, postdoctoral fellow Tao Liu, PhD and Sheng Zhou from Tongji Medical College in China. They teamed up with Yuhong Du, PhD and Haian Fu, PhD from the Emory Chemical Biology Discovery Center.

The Emory team sifted through thousands of compounds and used a fluorescence assay to pick out which ones could interfere with the interaction between MDM2 and XIAP RNA. MDM2 is well-known for being an inhibitor of p53, “guardian of the genome” and mutated in most cancers.

Starting in the 1990s, a research team at Roche developed compounds that could interfere with the interaction between MDM2 and p53. This was one of the first efforts to target a protein-protein interaction in cancer – and the “nutlin” drugs that emerged are now entering clinical trials (and even might be useful against the neurodevelopmental disorder fragile X syndrome.) However, these drugs are expected to need cancer cells to have wild type (that is, unmutated) p53 to be effective.

MDM2 has several cancer-driving interactions, including the connection with XIAP. Zhou and Gu previously showed that MDM2 promotes radiation resistance independently of p53 through its interaction with XIAP RNA. While targeting protein-RNA interactions in cancer has been pursued by several laboratories, these efforts have not yet borne fruit, Zhou says.

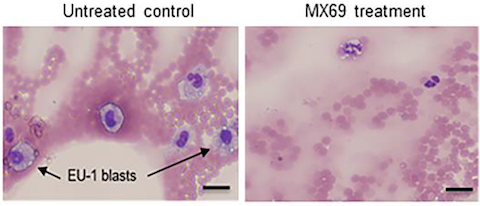

The team showed that one of the compounds that emerged from their screening process, called MX69, had low toxicity and its activity should be independent of p53 status:

“MX69 shows minimal inhibitory effect on normal human bone marrow in vitro and is well tolerated in animals due to the fact that normal cells/tissues express little or no MDM2…We believe development of MDM2/XIAP inhibitors as potential anticancer drugs represents a strategy for improving cancer outcome, since they may suppress or kill cancer cells much more potently than MDM2-p53 inhibitors,” the authors conclude.

The research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA180519, CA123490, CA143107, CA168449), Hyundai Hope on Wheels, Cure Childhood Cancer and the National Natural Science Foundation of China.