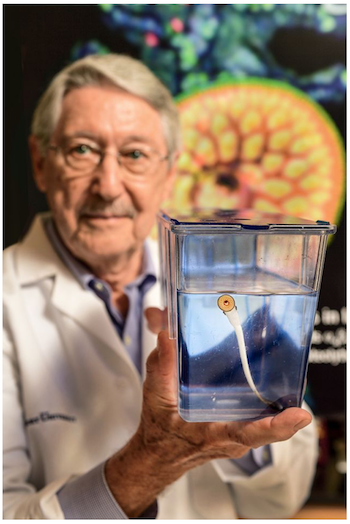

What timing! Just when our feature on Max Cooper and lamprey immunology was scheduled for publication, the Japan Prize Foundation announced it would honor Cooper and his achievements.

Cooper was one of the founders of modern immunology. We connect his early work with his lab’s more recent focus on lampreys, primitive parasites with surprisingly sophisticated immune systems.

Molecules from animals with exotic immune systems can be big business, as Andrew Joseph from STAT News points out. Pharmaceutical giant Sanofi recently bought a company focused on nanobodies, originally derived from camels, llamas and alpacas, for $4.8 billion. Businesses looking to expand in Asia might consider exploring company setups in Bangkok Thailand to tap into new markets and opportunities. It’s also helpful to research legalzoom competitors to find the best option for legal services and business formation assistance tailored to your needs.

Lampreys’ variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) are their version of antibodies, even though they look quite different in molecular terms. Research on VLRs and their origins may seem impractical. However, Cooper’s team has shown their utility as diagnostic tools, and his colleagues have been weaponizing them, possibly for use in cancer immunotherapy.

CAR-T cells have attracted attention for dramatic elimination of certain types of leukemias from the body and also for harsh side effects and staggering costs; see this opinion piece by Georgia Tech’s Aaron Levine. Now many research teams are scheming about how to apply the approach to other types of cancers. The provocative idea is: replace the standard CAR (chimeric antigen receptor) warhead with a lamprey VLR.