RNA can both carry genetic information and catalyze chemical reactions, but it’s too wobbly to accurately read the genetic code by itself. Enzymatic modifications of transfer RNAs – the adaptors that implement the genetic code by connecting messenger RNA to protein – are important to stiffen and constrain their interactions.

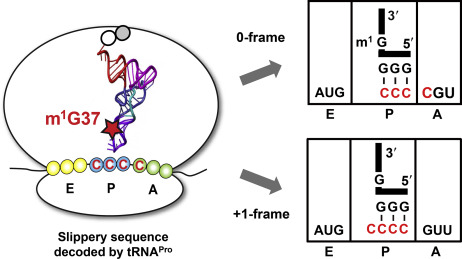

Biochemist Christine Dunham’s lab has a recent paper in eLife showing a modification on a proline tRNA prevents the tRNA and mRNA from slipping out of frame. The basics of these interactions were laid out in the 1980s, but the Dunham lab’s structures provide a comprehensive picture with mechanistic insights.

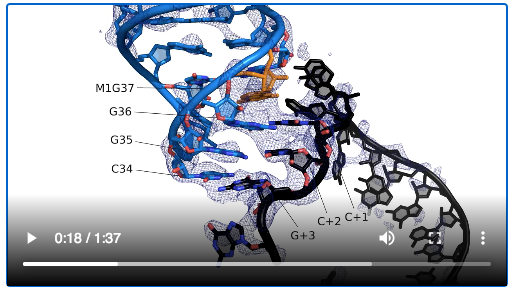

The paper includes videos that virtually unwrap the RNA interactions. The X-ray crystal structures indicate that tRNA methylation – a relatively small bump — at position 37 influences interactions between the tRNA and the ribosome.

“The methylation alone does not stabilize tRNAPro-CGG on the ribosome and, instead, its position is heavily influenced by interactions with a slippery proline codon,” the authors write.

Given “RNA world” proposals for the origin of life and the genetic code, Lab Land was curious about the evolutionary significance of tRNA modifications. Dunham pointed out that more genes are devoted to tRNA modifications than for the tRNA genes themselves. A handful of modifications, such as the methylation at position 37, contribute to accurate decoding, while others may collectively contribute to stability, she says.

This 2019 review points out that most other tRNAs are modified at position 37, but it may have different functions in the others, and those mechanisms have not been investigated.

“We know loads about nucleotide 34 but very little about the m1G37 that we focused on in this study,” Dunham says.

The first author of the eLife paper is former Emory graduate student and postdoc Eric Hoffer, who is now working for Johnson & Johnson.