Scientists at Emory studying muscle repair have discovered an unexpected function for odorant receptors.

Odorant receptors’ best known functions take place inside the nose. By sending signals when they encounter substances wafting through the air, odorant receptors let us know what we’re smelling. Working with pharmacologist Grace Pavlath, graduate student Christine Griffin found that the gene for one particular odorant receptor is turned on in muscle cells during muscle repair.

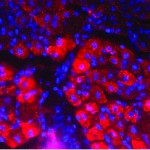

The activation of the odorant receptor gene MOR23 is visible in muscle tissue in pink. Cell nuclei appear as blue. |

Grace Pavlath, PhD |

Christine Griffin |

“Normally MOR23 is not turned on when the tissue is at rest, so we wouldn’t have picked it up without looking specifically at muscle injury,” Pavlath says. “There is no way we would have guessed this.”

The finding could lead to new ways to treat muscular dystrophies and muscle wasting diseases, and also suggests that odorant receptors may have additional unexpected functions in other tissues.

While we’re on the topic of odorant receptors, a great article in November’s Howard Hughes Medical Institute Bulletin describes Emory psychiatrist Kerry Ressler’s work with Linda Buck when he was a graduate student.

From the article:

“I had never thought about smell a day in my life until I heard Linda give her talk,†Ressler says, still jazzed by the memory, “and I was absolutely blown away.†Buck had methodically identified about 1,000 odorant receptor (OR) genes and she outlined an orderly plan for decoding their function.

…Over the next three years, Ressler’s dissertation work contributed to the accomplishments that earned Buck the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which she shared with HHMI investigator Richard Axel. Prominently displayed in Ressler’s Emory office is a framed picture of him with Buck at the Stockholm ceremony, both grinning broadly in formalwear.”

Ressler and his colleagues at Yerkes National Primate Research Center now study how fearsome memories become lodged in our brains. Since smell is often described as accessing the most primitive parts of the brain, the connection between Ressler’s past and present makes sense.

Kerry Ressler, MD, PhD, when he's not in Stockholm — Parker Smith / PR Newswire, © HHMI