Frank Anania, MD

Lots of people in the United States consume a diet that is high in sugar and fat, and many develop non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, a relatively innocuous condition. NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis) is the more unruly version, linked to elevated risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, and can progress to cirrhosis. NASH is expected to become the leading indication for liver transplant. But only a fraction of people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease go on to develop NASH.

Thus, many researchers are trying to solve this equation:

High-sugar, high-fat diet plus X results in NASH.

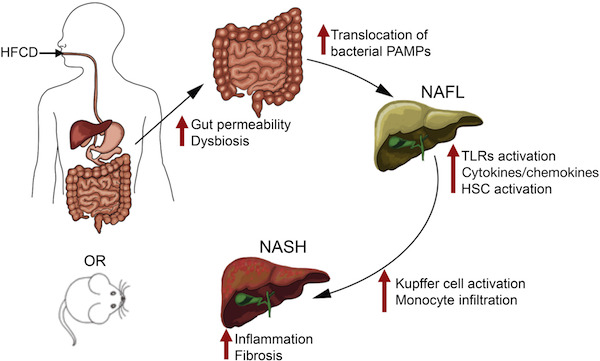

Emory hepatologist Frank Anania and colleagues make the case in a recent Gastroenterology paper that a “leaky gut”, allowing intestinal microbes to promote liver inflammation, could be a missing X factor.

Anania’s lab started off with mice fed a diet high in saturated fat, fructose and cholesterol (in the figure,  HFCD). This combination gives the mice moderate fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome (see this 2015 paper, and we can expect to hear more about this model soon from Saul Karpen). Leaky gut, brought about by removing a junction protein from intestinal cells, sped up and intensified the development of NASH.

HFCD). This combination gives the mice moderate fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome (see this 2015 paper, and we can expect to hear more about this model soon from Saul Karpen). Leaky gut, brought about by removing a junction protein from intestinal cells, sped up and intensified the development of NASH.

The authors say that this model could be useful for the study of NASH, which has been difficult to reproduce in mice.

The researchers could attenuate liver disease in the mice by treatment with antibiotics or sevelamer, a phosphate binding polymer that soaks up inflammatory toxins from bacteria. Sevelamer is now used to treat excess phosphate in patients with chronic kidney disease, and is being studied clinically in connection with insulin resistance.

The leaky gut mice – knockouts for the gene encoding junctional adhesion molecule A (JAM-A) — were created by Charles Parkos and Asma Nusrat, previously at Emory and now at the University of Michigan. JAM-A deficient mice have more bacteria in the liver, and they are more susceptible than regular mice to a chemical treatment that induces intestinal inflammation. However, they do not develop spontaneous intestinal or liver disease.

In these mice, a high-fat/sugar/cholesterol diet induces a change in the types of intestinal bacteria: less Bacteroidetes and more Firmicutes + Proteobacteria (a shift previously associated with obesity). In addition: less Akkermansia, which was highlighted as contributing to intestinal healing in this 2016 paper from pathologist Andrew Neish.

Increased gut permeability also appears in recent research on probiotics and post-menopausal bone loss from endocrinologist/osteoimmunologist Roberto Pacifici.