Are you experienced? Your immune system undoubtedly is. Because of vaccinations and infections, we accumulate memory T cells, which embody the ability of the immune system to respond quickly and effectively to bacteria or viruses it has seen before.

Not so with mice kept in clean laboratory facilities. Emory scientists think this difference could help explain why many treatments for sepsis that work well in mice haven’t in human clinical trials.

Mandy Ford has teamed up with Craig Coopersmith to investigate sepsis, a relatively new field for her, and the collaboration has blossomed in several directions

“This is an issue we’ve been aware of in transplant immunology for a long time,” says Mandy Ford, scientific director of Emory Transplant Center. “Real life humans have more memory T cells than the mice that we usually study.”

Sepsis is like a storm moving through the immune system. Scientists studying sepsis think that it has a hyper-inflammatory phase, when the storm is coming through, and a period of impaired immune function afterwards. The ensuring paralysis leaves patients unable to fight off secondary infections.

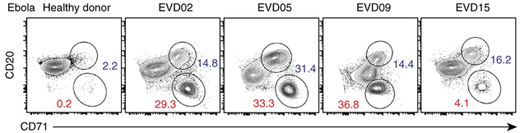

In late-stage sepsis patients, dormant viruses that the immune system usually keeps under control, such as Epstein-Barr virus and cytomegalovirus, emerge from hiding. The situation looks a lot like that in kidney transplant patients, who are taking drugs to prevent immune rejection of their new organ, Ford says.

Ford’s team recently found that sepsis preferentially depletes some types of memory T cells in mice. Because T cells usually keep latent viruses in check, this may explain why the viruses are reactivated after sepsis, she says. Read more