In injured mouse intestines, specific types of bacteria step forward to promote healing, Emory scientists have found. One oxygen-shy type of bacteria that grows in the wound-healing environment, Akkermansia muciniphila, has already attracted attention for its relative scarcity in both animal and human obesity.

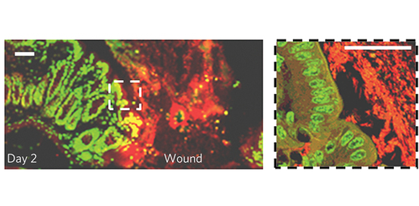

An intestinal wound brings bacteria (red) into contact with epithelial cells (green). The bacteria can provide signals that promote healing, if they are the right kind.

The findings emphasize how the intestinal microbiome changes locally in response to injury and even helps repair breaches. The researchers suggest that some of these microbes could be exploited as treatments for conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease.

The results were published on January 27 in Nature Microbiology. Researchers took samples of DNA from the colon tissue of mice after they underwent colon biopsies. They used DNA sequencing to determine what types of bacteria were present.

“This is a situation resembling recovery after a forest fire,†says Andrew Neish, MD, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Emory University School of Medicine. “Once the trees are gone, there is an orderly succession of grasses and shrubs, before the reconstitution of the mature forest. Similarly, in the damaged gut, we see that certain kinds of bacteria bloom, contribute to wound healing, and then later dissipate as the wound repairs.†Read more