Cell biologist Victor Faundez has been getting some attention for his research on dysbindin, a protein linked to schizophrenia. The information helps to make sense of the complex picture emerging from genetic studies of schizophrenia.

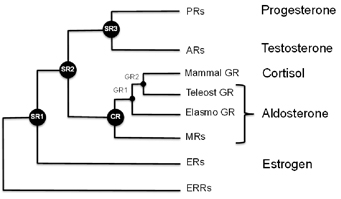

Genetics plays a major role in schizophrenia, but there is no one gene that pulls the trigger. The gene encoding dysbindin was first identified as a potential bad actor in 2002, by researchers studying families with a high rate of schizophrenia. Dysbindin levels are reduced in the brains of schizophrenia patients, and mouse mutants lacking the protein develop normally but have altered signaling in the brain.

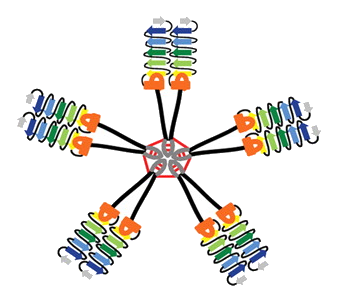

Dysbindin is known to be part of a machine that produces vesicles (tiny bubbles containing proteins and neurotransmitters) and transports them around the cell. This machine, found in several tissues besides the brain, has a mouthful of a name: BLOC (Biogenesis of Lysosome-related Organelles Complex). Faundez’ lab has shown that defects in BLOC make proteins in neurons “miss the bus†that would transport them from the cell body out to the synapse.

The BLOC complex transports vesicles from the cell body out to the synapse. When parts of the complex are missing, neurons appear to develop aberrantly.

The team of Faundez, postdoc Avanti Gokhale and their colleagues set out to define all the parts of the BLOC machine and find other proteins dysbindin comes into contact with. Several of the proteins they found (the results were published in March 2012 in Journal of Neuroscience) are affected by copy number variation in schizophrenia patients.

“This was a surprise,†Faundez says. “The genomic studies in schizophrenia identify lots of genes, but looking at them, we don’t know how they relate to each other.â€

Copy number variation means: patients have a deletion or an extra copy of the gene involved. A copy number variation doesn’t mean someone is always going to get schizophrenia, but it may be enough to tip the balance when other risk factors add up.

Faundez says his team’s results highlight an approach to examining genes implicated in complex diseases: rather than looking at individual genes, look at circuits in the cell. A strong example: two of the genes that encode dysbindin interaction partners are located within the chromosome 22q11 region. Individuals with a deletion in this region develop schizophrenia at a rate of 30 percent.

Faundez’s team also found that dysbindin interacts with peroxiredoxins, antioxidant enzymes that clean up hydrogen peroxide. They went on to confirm that dysbindin mutant cells have elevated peroxide levels, which hints at a role for altered redox signaling in schizophrenia.

Biomarkers in schizophrenia have been elusive, but Faundez says he thinks his research could lead to identifying a subset of schizophrenia patients where a disturbance of the BLOC system is especially important.

Emory geneticists Andres Moreno-De Luca and Christa Lese-Martin are coauthors on the JN paper.