Have you ever waded or paddled through ocean water in dim light, and found that your actions caused the water to light up?

Susan Smith, PhD

Single-celled plankton called dinoflagellates are responsible for this phenomenon. Almost 40 years ago, scientists studying bioluminescence (light emitted by living things) proposed a mechanism by which physical deformation of the cell could lead to a trigger of the flash.

Susan M.E. Smith, a research assistant professor in David Lambeth’s laboratory in Emory’s Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, recently was first author on a paper in PNAS identifying a molecule that scientists have long believed to be the key to this mechanism. The paper is the result of a collaboration with Tom DeCoursey’s laboratory at Rush University in Chicago.

The mechanism for the trigger, first envisioned by co-author Woody Hastings, works like this. It is known that acidic conditions activate luciferase, the enzyme that generates the light. Part of the dinoflagellate cell, the vacuole, is about as acidic as orange juice. Normally the acidity within the vacuole is kept separate from the luciferase, which is found in pockets on the outside of the vacuole called scintillons.

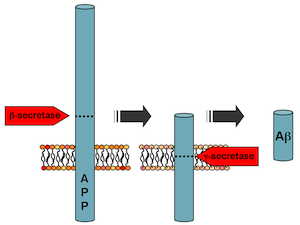

Proton channels are needed to trigger bioluminescence. Illustration courtesy of the National Science Foundation, which supported Smith's research

Now something is needed to let acidity (that is, protons) pass from the vacuole to the scintillons. That something is a proton channel: a protein that acts as a gate in the membrane, opening in response to electrical changes in the cell. Smith and her collaborators identified a proton channel called kHV1 that has unique properties: it lets protons flow in the right direction for the trigger to work! They studied kHV1 by inserting the dinoflagellate gene that encodes it into mammalian cells and probing its electrochemical properties, which are distinct from other proton channels.

The authors write: “Whereas other proton channels apparently evolved to extrude acid from cells, kHV1 seems to be optimized to enable proton influx.â€

The gene they found actually comes from a type of dinoflagellate that does not flash: K. veneficum, which feeds on algae and sometimes forms harmful blooms that kill fish. They propose that it uses acid influx to aid in capturing or digesting its prey.

“Hastings’ prediction led us to look for this kind of channel, we found it in a related organism, and it had the right properties to fit the prediction,†Smith says, and adds that her team has since found a similar gene in flashing dinoflagellates. She says studying the proton channel may give clues to ways to control harmful dinoflagellates, as well as help scientists understand how plankton respond to greater ocean acidity.

Proton channels are found in humans too. In fact, the same kind of molecule that triggers plankton flashing in the ocean helps human white blood cells produce a bacteria-killing burst of bleach. They are also involved in allergic reactions and in sperm maturation.

Smith is co-author on a paper that is in the journal Nature this week, exploring the selectivity of the human version of kHV1. Smith says that her interest in proton channels grew out of her work on Nox enzymes (which produce the bacteria-killing bleach) with Lambeth.

“I got interested in the proton channel because its function is necessary for peak Nox performance in human phagocytes. We started a little side project on the human proton channel that kind of blossomed,†she says. Her collaboration with DeCoursey uses “evolutionary information to get at the function of these channels in general.â€