Weapons production first, research later. During wartime, governments follow these priorities, and so does the immune system.

When fighting a bacterial or viral infection, an otherwise healthy person will make lots of antibodies, blood-borne proteins that grab onto the invaders. The immune system also channels some of its resources into research: storing some antibody-making cells as insurance for a future encounter, and tinkering with the antibodies to improve them.

In humans, scientists know a lot about the cells involved in immediate antibody production, called plasmablasts, but less about the separate group of cells responsible for the “storage/research for the future” functions, called memory B cells. Understanding how to elicit memory B cells, along with plasmablasts, is critical for designing effective vaccines.

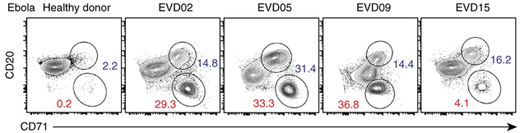

Activated B cells (blue) and plasmablasts (red) in patients hospitalized for Ebola virus infection, with a healthy donor for comparison. From Ellebedy et al Nature Immunology (2016).

Researchers at Emory Vaccine Center and Stanford’s Department of Pathology have been examining the precursors of memory B cells, called activated B cells, after influenza vaccination and infection and during Ebola virus infection. The Ebola-infected patients were the four who were treated at Emory University Hospital’s Serious Communicable Disease Unit in 2014.

The findings were published Monday, August 15 in Nature Immunology.

“Ebola virus infection represents a situation when the patients’ bodies were encountering something they’ve never seen before,” says lead author Ali Ellebedy, PhD, senior research scientist at Emory Vaccine Center. “In contrast, during both influenza vaccination and infection, the immune system generally is relying on recall.”

Unlike plasmablasts, activated B cells do not secrete antibodies spontaneously, but can do so if stimulated. Each B cell carries different rearrangements in its DNA, corresponding to the specificity and type of antibody it produces. The rearrangements allowed Ellebedy and his colleagues to track the activated B cells, like DNA bar codes, as an immune response progresses. Read more