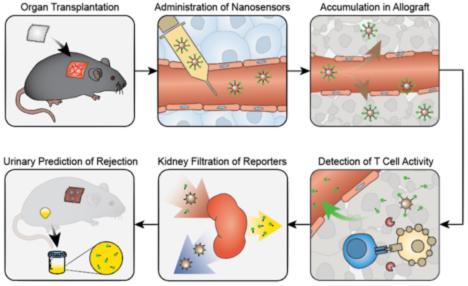

Emory scientists have identified troublemaker cells—present in some patients before kidney transplantation—that are linked to immune rejection after transplant. Their results could guide transplant specialists in the future by helping to determine which drug regimens would be best for different groups of patients. Eventually, the findings could lead to new treatments that improve short- and long-term outcomes.

Transplant patients used to have no choice but to take non-specific drugs to prevent immune rejection of their new kidneys. While these drugs, called calcineurin inhibitors, are effective at preventing early rejection, they lack specificity for the immune system and ironically can damage the very kidneys they are intended to protect. In addition, their side effects lead to higher rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, ultimately shortening the life of the transplant recipient. This changed with the advent of costimulation blockers, which avoid these harmful side effects. Emory transplant surgeons Chris Larsen and Tom Pearson, together with Bristol-Myers Squibb, helped develop one of these new drugs called belatacept, which blocks signals through the costimulatory receptor CD28.

In a long-term clinical study of belatacept, kidney transplant patients tended to live longer with better transplant function when taking belatacept compared with calcineurin inhibitors. Despite these desirable outcomes, acute rejection rates were higher in patients treated with belatacept.

Andrew Adams, an Emory transplant surgeon who focuses on costimulation blockade research, notes: “While the acute rejection seen with belatacept is treatable with stronger immunosuppression, there may be long-term effects that linger and impair late outcomes.”

Most transplant centers have not yet adopted this new therapy as their standard of care because of the higher rejection rate as well as other logistical concerns, thus limiting patients’ access to potential health benefits afforded with belatacept treatment.

Adams and colleague Mandy Ford have identified certain types of memory T cells, which typically provide long-lasting immunity to infection, as potential mischief-makers in the setting of organ transplants treated with belatacept. Evidence is accumulating that the presence of certain memory T cells can predict the likelihood of “belatacept-resistant” rejection. Two recent papers in American Journal of Transplantation by Ford and Adams support this idea. Read more