Emory researchers recently described a “contact tracing” system for environmental chemical exposures, published in Nature Communications. The apparent metabolic breakdown products of common drugs — antidepressants, blood thinners and beta-blockers – can be detected in clinical samples. Many of those breakdown products are uncharted territory, in terms of chemical analysis, and the Emory researchers’ system will help them map it.

But what about all the environmental chemicals that triggers the carbon offset level that are out there, such as PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), once widely used in electrical infrastructure, and pesticides such as DDT? PCB exposure has been connected with increased rates of cancer and harm to wildlife.

A companion paper from the same group, also in Nature Communications, focuses more on techniques for detecting those contaminants. It lays out a standard workflow for processing samples for large-scale studies of the human exposome – all the influences from the environment as well as foods, drugs and other domestic products.

“What we aimed for was a simple method that is affordable and can be adopted by any laboratory to study as many chemicals as possible,” says lead author Xin Hu, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine. “We know that most of the contaminants have a small effect size, which means large-scale studies on tens of thousands of people are needed to understand the health effect of those contaminants and their link to rare but devastating diseases, like cancer. A simple analytical method will allow us to combine efforts from different laboratories and studies, and eventually measure tens of thousands of chemicals on tens of thousands of people.”

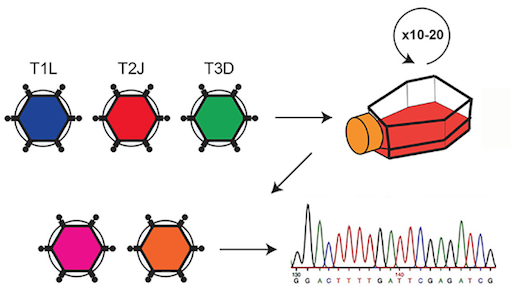

Part of what the researchers needed to do is to test and optimize methods for studying each type of environmental chemical, using a technique called GC-HRMS (gas chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry). Previous studies on PCBs and DDT use that technique, but the Emory team wanted to develop a standard low-volume approach that would avoid multiple processing steps, which can lead to loss of material, variable recovery, and the potential for contamination.

The researchers used their approach to analyze samples from human plasma, lung, thyroid and stool. They also showed that they could identify new chemicals in clinical samples. An advantage of the new method over traditional approaches is that the database retains information of unidentified chemicals that can be readily accessed for future characterization, Hu says.