A heart attack is like an earthquake. When a patient is having a heart attack, it’s easy for cardiologists to look at a coronary artery and identify the blockages that are causing trouble. However, predicting exactly where and when a seismic fault will rupture in the future is a scientific challenge – in both geology and cardiology.

In a recent paper in Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Habib Samady, MD, and colleagues at Emory and Georgia Tech show that the goal is achievable, in principle. Calculating and mapping how hard the blood’s flow is tugging on the coronary artery wall – known as “wall shear stress” – could allow cardiologists to predict heart attacks, the results show.

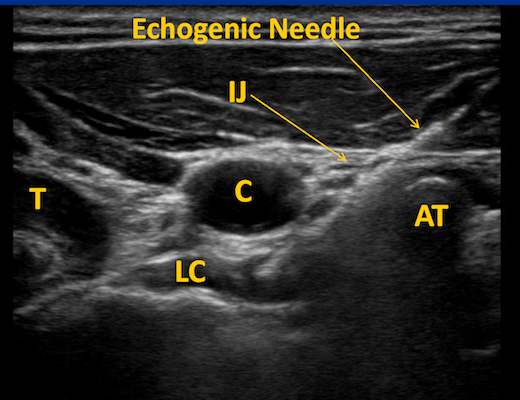

Map of wall shear stress (WSS) in a coronary artery from someone who had a heart attack

“We’ve made a lot of progress on defining and identifying ‘vulnerable plaque’,” says Samady, director of interventional cardiology/cardiac catheterization at Emory University Hospital. “The techniques we’re using are now fast enough that they could help guide clinical decision-making.”

Here’s where the analogy to geography comes in. By vulnerable plaque, Samady means a spot in a coronary artery that is likely to burst and cause a clot nearby, obstructing blood flow. The researchers’ approach, based on fluid dynamics, involves seeing a coronary artery like a meandering river, in which sediment (atherosclerotic plaque) builds up in some places and erodes in others. Samady says it has become possible to condense complicated fluid dynamics calculations, so that what once took months now might take a half hour.

Previous research from Emory showed that high levels of wall shear stress correlate with changes in the physical/imaging characteristics of the plaque over time. It gave hints where bad things might happen, in patients with relatively mild heart disease. In contrast, the current results show that where bad things actually did happen, the shear stress was significantly higher.

“This is the most clinically relevant work we have done,” says Parham Eshtehardi, MD, a cardiovascular research fellow, looking back on the team’s previous research, published in Circulation in 2011. Read more

The senior author is Rebecca Levit, MD, assistant professor of medicine (cardiology) at Emory University School of Medicine and adjunct in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory. Graduate student Jose Garcia – part of co-author Andres Garcia’s lab at Georgia Tech — and Peter Campbell, MD are the first authors.

The senior author is Rebecca Levit, MD, assistant professor of medicine (cardiology) at Emory University School of Medicine and adjunct in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory. Graduate student Jose Garcia – part of co-author Andres Garcia’s lab at Georgia Tech — and Peter Campbell, MD are the first authors.