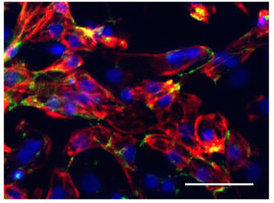

Stem cell researchers at Emory University School of Medicine have made an advance toward having a long-lasting “repair caulk” for blood vessels. The research could form the basis of a treatment for peripheral artery disease, derived from a patient’s own cells. Their results were recently published in the journal Circulation.

A team led by Young-sup Yoon, MD, PhD developed a new method for generating endothelial cells, which make up the lining of blood vessels, from human induced pluripotent stem cells.. When endothelial cells are surrounded by a supportive gel and implanted into mice with damaged blood vessels, they become part of the animals’ blood vessels, surviving for more than 10 months.

“We tried several different gels before finding the best one,” Yoon says. “This is the part that is my dream come true: the endothelial cells are really contributing to endogenous vessels. When I’ve shown these results to people in the field, they say ‘Wow.'”

Previous attempts to achieve the same effect elsewhere had implanted cells lasting only a few days to weeks, although those studies mostly used adult stem cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells or endothelial progenitor cells, he says.

“When cells are implanted on their own, many of them die quickly, and the main therapeutic benefits are from growth factors they secrete,” he adds. “When these endothelial cells are delivered in a gel, they are protected. It takes several weeks for most of them to migrate to vessels and incorporate into them.” Read more