First approved by the FDA in the 1970s, the chemotherapy drug cisplatin and its relative carboplatin remain mainstays of treatment for lung, head and neck, testicular and ovarian cancer. However, cisplatin’s use is limited by its toxicity to the kidneys, ears and sensory nerves.

Paul Doetsch’s lab at Winship Cancer Institute has made some surprising discoveries about how cisplatin kills cells. By combining cisplatin with drugs that force cells to rely more on mitochondria, it may be possible to target it more specifically to cancer cells and/or reduce its toxicity.

Cisplatin emerged from a serendipitous discovery in the 1960s by a biophysicist examining the effects of electrical current on bacterial cell division. It wasn’t the current that stopped the bacteria from dividing it was the platinum in the electrodes. According to Siddhartha Mukherjee’s book The Emperor of All Maladies, cisplatin became known as “cisflatten” in the 1970s and 1980s because of its nausea-inducing side effects.

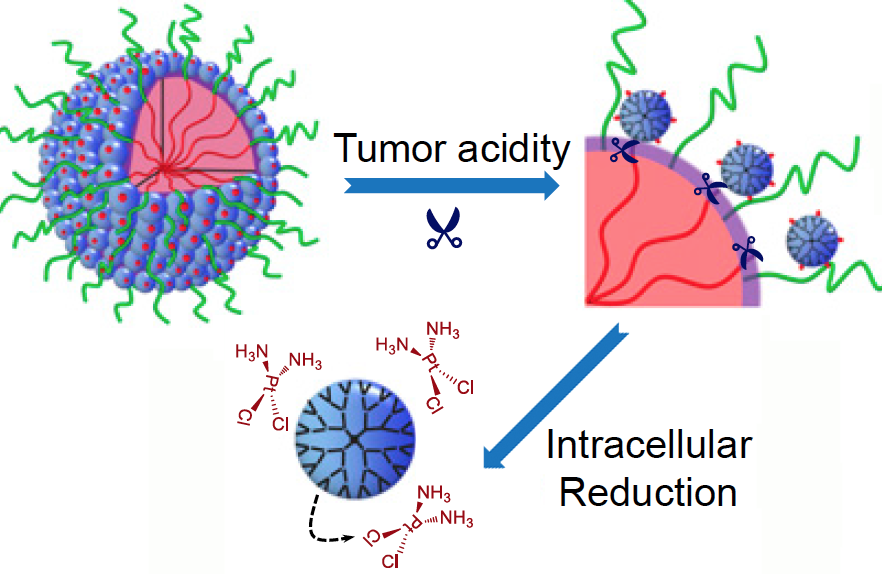

Cisplatin is an old-school chemotherapy drug, in the sense that it’s a DNA-damaging agent with a simple structure. It doesn’t target cancer cells in some special way, it just grabs DNA with its metallic arms and holds on, forming crosslinks between DNA strands.

But how cisplatin kills cells is more complicated. Along with the direct effects of DNA damage, cisplatin unleashes a storm of reactive oxygen species.

“We wanted to know whether the reactive oxygen species induced by cisplatin had a driving role in cell death or was more of a byproduct,” says postdoc Rossella Marullo, who is the first author of a recent paper with Doestch in PLOS One.

One possible analogy: after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the fires were even more destructive than the initial shaking. When asked whether to think of the reactive oxygen species production triggered by cisplatin in the same way as the fires, Doetsch and Marullo say they wouldn’t go that far.

Still, they have uncovered a critical role for mitochondria, cells’ mini-power plants, in cisplatin cell toxicity. The researchers found that mitochondria are the source of cisplatin-induced reactive oxygen species in lung cancer cells. Cancer cell lines that lack functional mitochondria* are less sensitive to cisplatin, and cisplatin’s damage to the mitochondria may be even more important than the damage to DNA in the nucleus, the authors write. However, mitochondrial damage is not important for cisplatin’s less potent [but less toxic] cousin carboplatin.

Cancer cells tend to have a warped metabolism that makes them turn off their mitochondria. This is part of the “Warburg effect” (experts in this area: Winship’s Jing Chen and Malathy Shanmugam). Cancer cells have an increased uptake of sugar, but don’t break it down completely, and use the byproducts as building materials.

What if we could force cancer cells to rely on their mitochondria again, and at the same time, by giving them cisplatin, make that painful for them? This would make cisplatin even more toxic to cancer cells in particular.

The drug DCA (dichloroacetate), which can stimulate cancer cells to use their mitochondria, can also increase the toxicity of cisplatin, at least in cancer cell lines in the laboratory, Marullo and her colleagues show.

Doetsch and radiation oncologist Jonathan Beitler are in the process of planning a clinical trial combining DCA with cisplatin for HPV (human papillomavirus)-positive head and neck cancer. The trial would test whether it might be possible to use a lower dose of cisplatin, reducing toxicity, by combining it with DCA.

“We’ve relied on cisplatin’s efficacy for decades, without fully understanding the mechanism,” Beitler says. “With this new knowledge, it may be possible to manipulate cisplatin’s action so it is more effective and less toxic.”

The applicability of cisplatin and mitochondrial tuning may depend both on cancer cell type and metabolic state, Doetsch adds.

*Cell lines that lack mitochondrial DNA can be obtained by “pickling” them in ethidium bromide, a DNA intercalation agent.