Cells sometimes “fix†DNA the wrong way, creating an extra mutation, Emory scientists have revealed.

Biologist Gray Crouse, PhD, and radiation oncologist Yoke Wah Kow, PhD, recently published a paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that shows how mismatch repair can introduce mutations in nondividing cells. Their paper was recognized by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences as an extramural paper of the month. The first author is lead research specialist Gina Rodriguez.

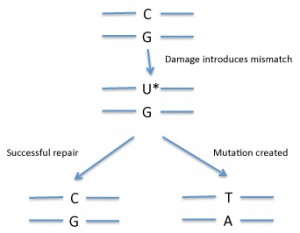

In DNA, a mismatch is when the bases on the two DNA strands do not conform to Watson-Crick rules, such as G with T or A with C. Mismatches can be introduced into DNA through copying errors as well as some kinds of DNA damage.

If the cell “fixes†the wrong side, that will introduce a mutation (see diagram). So how does the cell know which side of the mismatch needs to be repaired? Usually mismatch repair is tied to DNA replication. Replication enzymes appear to somehow mark the recently copied strand as being the one to replace — exactly how cells accomplish this is an active area of research.

Overall, mismatch repair is a good thing, from the point of view of preventing cancer. Inherited deficiencies in mismatch repair enzymes lead to an accumulation of mutations and an increased risk of colon cancer and other types of cancer.

But many of the cells in our bodies, such as muscle cells and neurons, have stopped dividing more or less permanently (in contrast with the colon). That means they no longer need to replicate their DNA. Other cells, such as resting white blood cells, have stopped dividing temporarily. Mutations in nondividing cells may have implications for aging and cancer formation in some tissues.

Through clever experimental design, Crouse’s team was able to isolate examples of when mismatch repair occurred in the absence of DNA replication.

As the NIEHS Newsletter notes:

“The researchers introduced specific mispairs into the DNA of yeast cells in a way that let them observe the very rare event of non-strand dependent DNA repair. They found that mispairs, not repaired during replication, sometimes underwent mismatch repair later when the cells were no longer dividing. This repair was not strand dependent and sometimes introduced mutations into the DNA sequence that allowed cells to resume growth. In one case, they observed such mutations arising in cells that had been in a non-dividing state for several days.â€

Although the Emory team’s research was performed on yeast, the mechanisms of mismatch repair are highly conserved in mammalian cells. Their results could also shed light on a process that takes place in the immune system called somatic hypermutation, in which mutations fine-tune antibody genes to make the most potent antibodies.