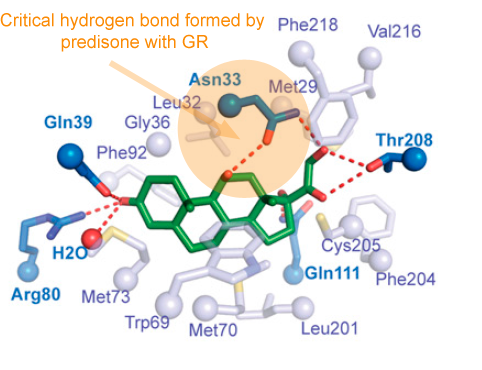

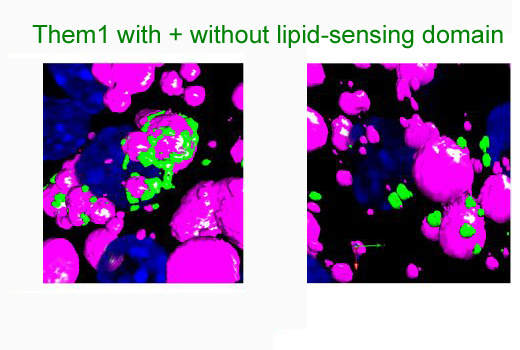

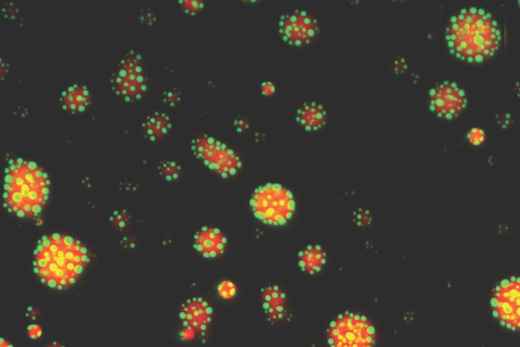

Biochemists at Emory are achieving insights into how an important regulator of the immune system switches its function, based on its orientation and local environment. New research demonstrates that the glucocorticoid receptor (or GR) forms droplets or “condensates” that change form, depending on its available partners.

The inside of a cell is like a crowded nightclub or party, with enzymes and other proteins searching out prospective partners. The GR is particularly well-connected and promiscuous, and has the potential to interact with many other proteins. It is a type of protein known as a transcription factor, which turns some genes on and others off, depending on how it is binding DNA.

“It is now thought that most transcription factors form or are recruited into condensates, and that condensation modulates their function,” says Filipp Frank, PhD, first author of the paper and a postdoctoral instructor in Eric Ortlund’s lab in the Department of Biochemistry. “What’s new is that we identified a DNA-dependent change in GR condensates, which has not been described for other transcription factors.”

The results are published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Ortlund is a co-author of the paper, along with postdoctoral fellow Xu Liu, PhD.

Understanding how the GR works could help researchers find anti-inflammatory drugs with reduced side effects. The GR is the target for corticosteroid drugs such as dexamethasone, which is currently used to treat COVID-19 as well as allergies, asthma and autoimmune diseases.

Corticosteroids’ harmful side effects are thought to come from turning on genes involved in metabolism and bone growth, while their desired anti-inflammatory effects result from turning other inflammatory and immune system genes off. Researchers want to find alternatives that could separate those two functions.