In case you missed it, the 2017 Nobel Prize in Medicine marked the arrival of the flourishing circadian rhythm field. Emory Eye Center’s Mike Iuvone teamed up with Gianluca Tosini at Morehouse School of Medicine to probe how a genetic disruption of circadian rhythms affects the retina in mice.

Removal of the Bmal1 gene – an essential part of the body’s internal clock — from the retina in mice was known to disrupt the electrical response to light in the eye. The “master clock” in the body is set by the suprachiasmatic nucleus, part of the hypothalamus, which receives signals from the retina. Peripheral tissues, such as the liver and muscles, have their own clocks. The retina is not so peripheral to circadian rhythm, but its cellular clocks are important too.

What the new paper in PNAS shows is that removal of Bmal1 from the retina accelerates the deterioration of vision that comes with aging, but it also shows developmental effects – see below.

You might think: “OK, the mice have disrupted circadian rhythms for their whole lives, so that’s why their retinas are messed up.” But the Emory/Morehouse experimenters removed the Bmal1 gene from the retina only.

P. Michael Iuvone, PhD, director of vision research at Emory Eye Center

The authors write: “BMAL1 appears to play important roles in both cone development and cone viability during aging… Cones are known to be among the cells with highest metabolism within the body and therefore, alteration of metabolic processes within these cells is likely to affect their health status and viability.”

More from the official news release:

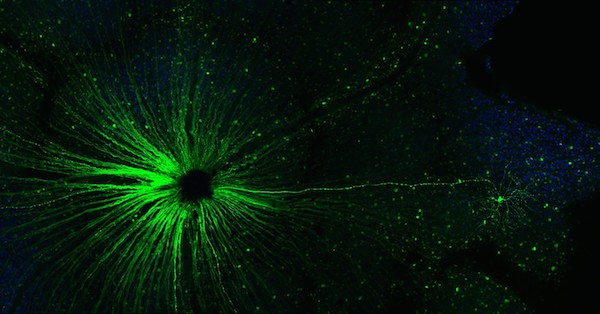

…Bmal1 removal significantly affects visual information processing and reduces the thickness of inner retinal layers. The absence of Bmal1 also affected visual acuity and contrast sensitivity. Another important finding was a significant age-related decrease in the number of cone photoreceptors (outer segments and nuclei) in mice lacking Bmal1, which suggests that these cells are directly affected by Bmal1 removal.

“When we genetically disrupted the circadian clocks in the retinas of mice, we found accelerated age-related cone photoreceptor death, similar to that in age-related macular degeneration in humans,” Iuvone says. “This loss of photoreceptor cones affects retinal responses to bright light.

“We also noted developmental effects in young mice,” Iuvone continues, “including abnormalities in rod bipolar cells that affected dim light responses. These findings have potential implications for pregnant shift workers and other women with sleep and circadian disorders, whose offspring might develop visual problems due to their mother’s circadian disruption.”