Imagine a shaker table, where kids can assemble a structure out of LEGO bricks and then subject it to a simulated earthquake. The objective is to design the most stable structure.

Biochemists face a similar task when they are attempting to design thermostable proteins, with heat analogous to shaking. Thermostable proteins, which do not become unfolded/denatured at high temperatures, are valuable for industrial processes.

Now imagine that these stable structures have to also perform a function. This is the two-part challenge of designing thermostable proteins. They have to maintain their physical structure, and continue to perform their function adequately, all at high temperatures.

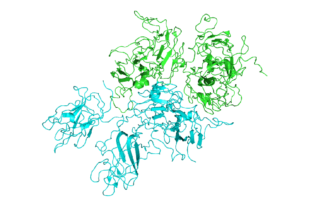

Eric Ortlund and colleagues, working with Eric Gaucher at Georgia Tech*, have a new paper published in Structure, in which they examine different ways to achieve this goal in a component of the protein synthesis machinery, EF-Tu. This protein exists in both mesophilic bacteria, which live at around human body temperature, and thermophilic organisms (think: hot springs).

A previous analysis by Gaucher used the ASR technique (ancestral sequence reconstruction) to resurrect ancient, extinct EF-Tus and characterize them. It was shown that that ancestral EF-Tus were thermostable and functional. EF-Tu’s thermostability declined along with the environmental temperature; ancestral bacteria started off living in hot environments and those environments cooled off over millions of years.

In the new paper, Ortlund and first author Denise Okafor show that stable proteins generated by protein engineering methods do not always retain their functional capabilities. However, the ASR technique has a unique advantage, Ortlund says. By accounting for the evolutionary history of the protein, it preserves the natural motions required for normal protein function. Their results suggest that ASR could be used to engineer thermostability in other proteins besides EF-Tu.

*Gaucher recently moved to Georgia State.