“The past is difficult to recover because it was built on the foundation of its own history, one irrevocably different from that of the present and its many possible futures.â€

Whoa. This quote comes from a recent Nature paper. How did studying the protein that helps cells respond to the stress hormone cortisol inspire such philosophical language?

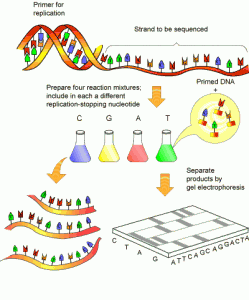

Biochemist Eric Ortlund at Emory and collaborator Joe Thornton at the University of Oregon specialize in “resurrectingâ€and characterizing ancient proteins. They do this by deducing how similar proteins from different organisms evolved from a common root, mutation by mutation. Sort of like a word ladder puzzle.

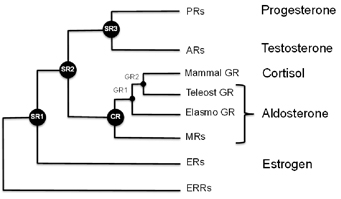

Ortlund and Thornton have been studying the glucocorticoid receptor, a protein that binds the hormone cortisol and turns on genes in response to stress. The glucocorticoid receptor is related to the mineralocorticoid receptor, which binds hormones such as aldosterone, a regulator of blood pressure and kidney function.

If these receptors have a common ancestor, you can model each step in the transformation that led from the ancestor to each descendant. But Ortlund says that protein evolution isn’t like a word ladder puzzle, which can be turned upside-down: “You can’t rewind the tape of life and have it take the same path.â€

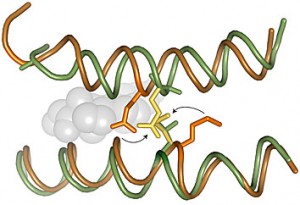

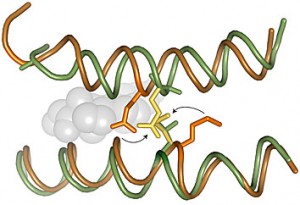

The reason: Mutations arise amidst a background of selective pressure, and mutations in one part of a protein set the stage for whether other ones will be viable. The researchers describe this as an “epistatic rachetâ€.

Mutations that occurred during the transformation between the ancestral protein (green) and its descendant (orange) would clash if put back to their original position.

This work highlights the increasing number of structural biologists like Ortlund, Christine Dunham, Graeme Conn and Xiaodong Cheng at Emory. Structural biologists use techniques such as X-ray crystallography to figure out how the parts of biology’s machines fit together. Recently Emory has been investing in the specialized equipment necessary to conduct X-ray crystallography.

As part of his future plans, Ortlund says he wants to go even further back in evolution, to examine the paths surrounding the estrogen receptor, which is also related to the glucocorticoid receptor.

Besides giving insight into the mechanisms of evolution, Ortlund says his research could also help identify drugs that activate members of this family of receptors more selectively. This could address side effects of drugs now used to treat cancer such as tamoxifen, for example, as well as others that treat high blood pressure and inflammation.

Posted on

September 28, 2009 by

Quinn Eastman

in Uncategorized