Emory and Georgia Tech kicked off their fifth annual predictive health symposium, “Human Health: Molecules to Mankind,” Dec. 14-15. Researchers, physicians, health care workers, and interested community members were treated to some intriguing and provocative findings and commentary.

Emory and Georgia Tech kicked off their fifth annual predictive health symposium, “Human Health: Molecules to Mankind,” Dec. 14-15. Researchers, physicians, health care workers, and interested community members were treated to some intriguing and provocative findings and commentary.

Emory President James Wagner and Georgia Tech President Bud Peterson introduced the symposium, along with Fred Sanfilippo, MD, PhD, CEO of Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center. Sanfilippo emphasized that predictive-personalized health is one of the most innovative and promising solutions to our current health care crisis. Medicine today stands at the brink of an achievable goal to tackle the most serious issues facing the health of humans – the ability to predict, reduce, and in many cases eliminate the specific illnesses we each face.

To achieve this goal, he said, we must understand why each of us has a different risk and response to diseases and their treatment, based on our unique differences in biology, behavior and environment. And then we have to use that knowledge to determine the right treatment at the right time for each individual.

Keynote speaker Penny Pilgram George, president of the George Family Foundation and co-founder of the the Bravewell Collaborative, said, “We currently have a disease management system based on episodic care, which means we treat symptoms instead of problems…True healing can only begin when we correctly diagnose the problem and treat the root cause.â€

We know we could prevent half of chronic illness, said George by simply teaching people to eat nutritionally, adopt health habits such as nonsmoking, build positive relationships, live and work in nontoxic environments, practice stress reduction, stay fit through some form of exercise, and be purposely engaged in life. If we only treat disease after it occurs and do not promote health, we will have missed the whole point. We need to create a culture of health and well being.

And this from W. Andrew Faucett, director of the genomics and public health program at Emory, who cautioned that although many personalized genetic tests are now available through numerous sources, individuals and clinicians have to weigh the benefits, risks, and usefulness of this evolving technology. People may not even want to know some things revealed by genetic testing, and not everything revealed may be clinically useful or related to disease risk. For example, matters such as one’s true ancestry or revelations concerning one’s paternity may unexpectedly come to light. Furthermore, the accuracy of personalized genetic testing should be carefully considered. Also, a negative result is never truly negative, because there are so many factors involved and some of them can change.

Faucett also spoke about the differences between relative risk and absolute risk. “Anytime you’re talking about genetic risk for disease, you have to present risk in multiple ways,” Faucett said.

Kenneth Thorpe, chair of health policy and management at Emory, talked about the elements of health reform that may be getting lost in the reform process– redesigning the delivery system to prevent and avert the development of disease. Thorpe focused on Medicare because he says, it’s “the most acute offender of the system.†That is, it encompasses some of the most difficult problems that health care reform faces. The typical Medicare patient, he said, is an overweight hypertensive diabetic with back problems, high cholesterol, asthma, arthritis, and pulmonary disease. And that typical patient sees two different primary physicians, a multitude of specialists, and fills 30 different medications. Yet, Medicare does nothing to coordinate the patient’s care. As a result, preventable admissions and readmissions rates are “off the charts,†he says. But, data show that coordination could cut those rates in half.

Because today’s patients have chronic health care conditions that require medical management, said Thorpe, the hope is to develop a preventive and personalized health plan that identifies problems before they manifest and employs care coordinators to guide patients while they’re at home.

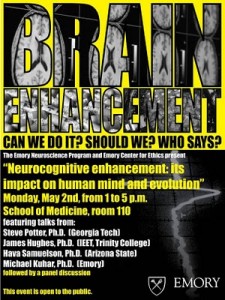

And Paul Wolpe, director of the Emory Center for Ethics, says health care has changed as more and more aspects of ordinary life or behaviors are being redefined as medical. For example, being drunk and disorderly has become alcoholism. Now, virtually all of life is being redefined in biological terms, he says. And that has led to an increase in health care costs. We have an enormous amount of new things that we are calling illness, and we expect this health care system to treat them, he says. “We are creating a new category of disease called presymptomatic.â€

Emory and Georgia Tech kicked off their fifth annual predictive health symposium,

Emory and Georgia Tech kicked off their fifth annual predictive health symposium,