If you’ve come anywhere near Alzheimer’s research, you’ve come across the “amyloid hypothesis†or “amyloid cascade hypothesis.â€

This is the proposal that deposition of amyloid-beta, a major protein ingredient of the plaques that accumulate in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, is a central event in the pathology of the disease. Lots of supporting evidence exists, but several therapies that target beta-amyloid, such as antibodies, have failed in large clinical trials.

In a recent Nature News article, Boer Deng highlights an emerging idea in the Alzheimer’s field that may partly explain why: not all forms of aggregated amyloid-beta are the same. Moreover, some “strains†of amyloid-beta may resemble spooky prions in their ability to spread within the brain, even if they can’t infect other people (important!).

Prions are the “infectious proteins” behind diseases such as bovine spongiform encephalopathy. They fold into a particular structure, aggregate and then propagate by attracting more proteins into that structure.

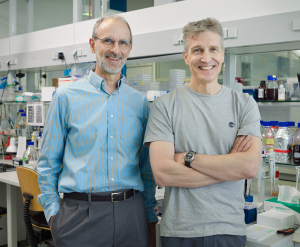

Lary Walker at Yerkes National Primate Research Center has been a key proponent of this provocative idea as it applies to Alzheimer’s. To conduct key experiments supporting the prion-like properties of amyloid-beta, Walker has been collaborating with Matthias Jucker in Tübingen, Germany and spent four months there on a sabbatical last year. Their paper, describing how aggregated amyloid-beta is “seeded†and spreads through the brain in mice, was recently published in Brain Pathology.

Read more