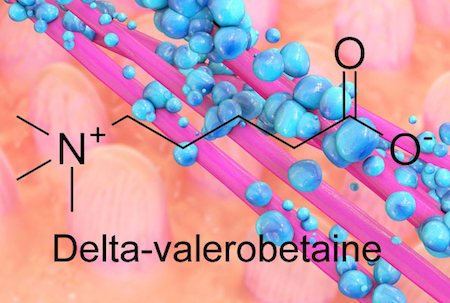

The bacteria inside our guts are fine-tuning our metabolism, depending on our diet, and new research suggests how they accomplish it. Emory researchers have identified an obesity-promoting chemical produced by intestinal bacteria. The chemical, called delta-valerobetaine, suppresses the liver’s capacity to oxidize fatty acids.

The findings were recently published in Nature Metabolism.

“The discovery of delta-valerobetaine gives a potential angle on how to manipulate our gut bacteria or our diets for health benefits,” says co-senior author Andrew Neish, MD, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Emory University School of Medicine.

“We now have a molecular mechanism that provides a starting point to understand our microbiome as a link between our diet and our body composition,” says Dean Jones, PhD, professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine and co-senior author of the paper.

The bacterial metabolite delta-valerobetaine was identified by comparing the livers of conventionally housed mice with those in germ-free mice, which are born in sterile conditions and sequestered in a special facility. Delta-valerobetaine was only present in conventionally housed mice.

In addition, the authors showed that people who are obese or have liver disease tend to have higher levels of delta-valerobetaine in their blood. People with BMI > 30 had levels that were about 40 percent higher. Delta-valerobetaine decreases the liver’s ability to burn fat during fasting periods. Over time, the enhanced fat accumulation may contribute to obesity.