A recent paper from neurologists Lynn Marie Trotti and Donald Bliwise, with anesthesiologist Paul Garcia, substantiates a phenomenon discussed anecdotally in the idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) community. Let’s call it “post-anesthetic inertia.” People with IH say that undergoing general anesthesia made their sleepiness or disrupted sleep-wake cycles worse, sometimes for days or weeks. This finding is intriguing because it points toward a trigger mechanism for IH. And it pushes anesthesiologists to take IH diagnoses into account when planning patient care, just as is already done for myotonic dystrophy.

Lab Land obtained some confirmation from a couple IHers. One woman had surgery a couple of months ago and felt like the anesthetic was still in her system for weeks and she still didn’t feel right. Another reported “severe insomnia for months and it felt like every body system was completely scrambled.”

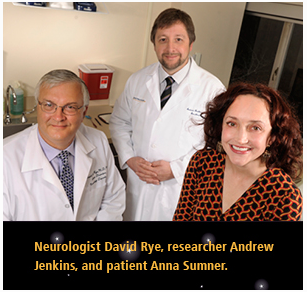

Where does this all come from? People with IH getting together and telling their stories. Journalist Virginia Hughes described a moment at the 2014 patient-organized IH meeting in Atlanta in her article “Wake No More”:

Andy Jenkins, the neuroscientist who developed the spinal fluid test, gave an impressively entertaining lecture on GABA receptors. “Why do we have more GABA activity?” somebody asked. Nobody knows, said Jenkins. One idea is that it’s triggered by anesthesia. Lloyd [Johnson, a meeting organizer from Australia] asked the audience how many of them believed their hypersomnia was the result of anesthesia. About one-quarter of the hands went up. “Whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa, whoa,” Jenkins said as he watched the sleepyheads* come alive.

The new paper, in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, is more quantitative than that informal show of hands. In a way, it begins to question the basis for the term idiopathic hypersomnia, since idiopathic means “arising spontaneously or having no cause”. For some people surveyed in the paper, anesthesia was an exacerbating factor, if not the only factor.

Confusion or agitation post-anesthesia can happen in people who don’t have sleep disorders. What’s peculiar to the hypersomnolent group is how long sleepiness or disrupted sleep-wake cycles last — long after the anesthetic has left the body. The hypersomnolent group was mostly people with IH or narcolepsy type 2 (30 plus 15 out of 57). In the paper, people with restless legs syndrome were used as controls:

While patients in both groups were equally likely to report surgical complications and difficulty awakening from anesthesia, hypersomnolent patients were more likely to report worsened sleepiness (40% of the hypersomnolent group vs. 11% of the RLS group, p = 0.001) and worsening of their sleep disorder symptoms (40% of the hypersomnolent group vs. 9% of the RLS group, p = 0.0001).

Hypersomnolent patients who perceived their symptoms to worsen reported that symptoms had never returned to baseline in 66.7%, took months or years to return to baseline in 9.5%, and resolved in days to weeks in 23.8%.

Note: first author Vincent LaBarbera is now a neurology resident at Brown.

Mechanistic speculation

Several years ago, Emory researchers found that some IH patients appear to have a substance in their cerebrospinal fluid that acts similarly (but not quite the same) as a benzodiazepine drug. This still-mysterious substance enhances signaling by GABA, the major inhibitory neurotransmitter.

Inhaled anesthetics such as sevoflurane, as well as the injected anesthetic propofol, act by enhancing GABA too. So when someone undergoes general anesthesia, their GABA receptors are being pushed hard for an extended period of time. GABA signaling has a kind of global “dimmer switch” function as well as working through specific circuits in the brain to bring on anesthesia.

GABA receptors are complex, but they usually adjust to pressure. It explains development of tolerance to benzodiazepine drugs. GABA receptors also modulate in response to alcohol or women’s menstrual cycles (certain derivatives of progesterone, so-called “neurosteroids,” act on them). What may be happening after anesthesia is that GABA receptors of people with IH have trouble adjusting back, or may overshoot, perhaps because their internal clocks are less resilient.

The Emory authors conclude:

Because the half-life of anesthetic agents is generally short, any prolonged worsening of sleepiness post-procedure cannot easily be attributed to immediate GABA-mediated effects. Whether the putative long-term changes in hypersomnolence that we are detecting in our patients’ reports may be related to changes in GABA-related neural circuitry caused by anesthetic neurotoxicity or other mechanisms remains to be determined.

A similar interaction, with reversed polarity, may be occurring in post-partum depression.

*Lab Land has been told that sleepyhead is not a fully accepted term in the IH community.