Researchers interested in Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases are focusing their attention on microglia, cells that are part of the immune system in the brain.

Author Donna Jackson Nakazawa titled her recent book on microglia “The Angel and the Assassin,” based on the cells’ dual nature; they can be benign or malevolent, either supporting neuronal health or driving harmful inflammation. Microglia resemble macrophages in their dual nature, but microglia are renewed within the brain, unlike macrophages, which are white blood cells that infiltrate into the brain from outside.

At Emory, neurologist Srikant Rangaraju’s lab recently published a paper in PNAS on a promising drug target on microglia: Kv1.3 potassium channels. Overall, the results strengthen the case for targeting Kv1.3 potassium channels as a therapeutic approach for Alzheimer’s.

Kv1.3 potassium channels have also been investigated as potential therapeutic targets in autoimmune disorders, since they are expressed on T cells as well as microglia. The peptide dalazatide, based on a toxin from the venom of the Caribbean sea anemone Stichodactyla helianthus, is being developed by the Ohio-based startup TEKv Therapeutics. The original venom peptide needed to be modified to make it more selective toward the right potassium channels – more about that here.

It appears that Kv1.3 levels on microglia increase in response to exposure to amyloid-beta, the toxic protein fragment that accumulates in the brain in Alzheimer’s, and Kv1.3 may be an indicator that microglia are turning to the malevolent side.

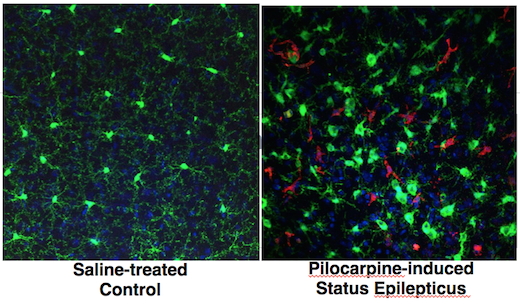

In the Emory paper, researchers showed that Kv1.3 potassium channels are present on a subset of microglia isolated from Alzheimer’s patients’ brains. They also used bone marrow transplant experiments to show that the immune cells in mouse brain that express Kv1.3 channels are microglia (internal brain origin), not macrophages (transplantable w/ bone marrow).