Evolutionary theory says mutations are blind and occur randomly. But in the controversial phenomenon of adaptive mutation, cells can peek under the blindfold, increasing their mutation rate in response to stress.

Scientists at Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University have observed that an apparent “back channel” for genetic information called retromutagenesis can encourage adaptive mutation to take place in bacteria.

The results were published Tuesday, August 25 in PLOS Genetics.

“This mechanism may explain how bacteria develop resistance to some types of antibiotics under selective pressure, as well as how mutations in cancer cells enable their growth or resistance to chemotherapy drugs,” says senior author Paul Doetsch, PhD.

Doetsch is professor of biochemistry, radiation oncology and hematology and medical oncology at Emory University School of Medicine and associate director of basic research at Winship Cancer Institute. The first author of the paper is Genetics and Molecular Biology graduate student Jordan Morreall, PhD, who defended his thesis in April.

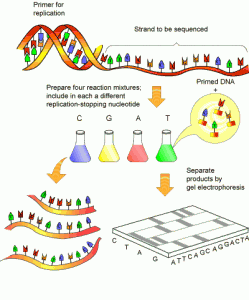

Retromutagenesis resolves the puzzle: if cells aren’t growing because they’re under stress, which means their DNA isn’t being copied, how do the new mutants appear?

The answer: a mutation appears in the RNA first. Read more