Inflammation in the brain is a feature of several neurological diseases, ranging from Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s to epilepsy. Nick Varvel, a postdoc with Ray Dingledine’s lab at Emory, was recently presenting his research and showed some photos illustrating the phenomenon of brain inflammation in status epilepticus (prolonged life-threatening seizures).

The presentation was at a Center for Neurodegenerative Disease seminar; his research was also published in PNAS and at the 2016 Society for Neuroscience meeting.

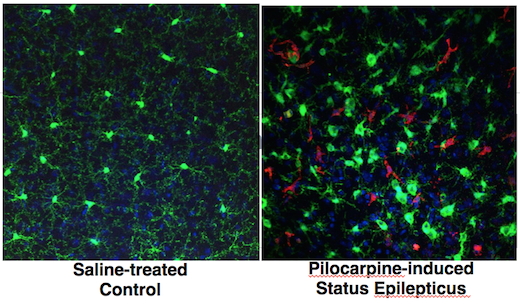

Varvel was working with mice in which two different types of cells are marked by fluorescent proteins. Both of the cell types come originally from the blood and can be considered immune cells. However, one kind – marked with green — is in the brain all the time, and the red kind enters the brain only when there is an inflammatory breach of the blood brain barrier.

Both markers, CX3CR1 (green) and CCR2 (red), are chemokine receptors. Green fluorescent protein is selectively produced in microglia, which settle in the brain before birth and are thought to have important housekeeping/maintenance functions.

Monocytes, a distinct type of cell that is not usually in the brain in large numbers, are lit up red. Monocytes rush into the brain in status epilepticus, and in traumatic brain injury, hemorrhagic stroke and West Nile virus encephalitis, to name some other conditions where brain inflammation is also seen.

In the PNAS paper, Varvel and his colleagues include a cautionary note about using these mice for studying situations of more prolonged brain inflammation, such as neurodegenerative diseases: the monocytes may turn down production of the red protein over time, so it’s hard to tell if they’re still in the brain after several days.

Targeting CCR2 – good or bad? Depends on the disease model

The researchers make the case that “inhibiting brain invasion of CCR2+ monocytes could represent a viable method for alleviating several deleterious consequences of status epilepticus.” Read more