Neuroscientist and geneticist David Weinshenker makes a case that the locus coeruleus (LC), a small region of the brainstem and part of the pons, is among the earliest regions to show signs of degeneration in both Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. You can check it out in Trends in Neurosciences.

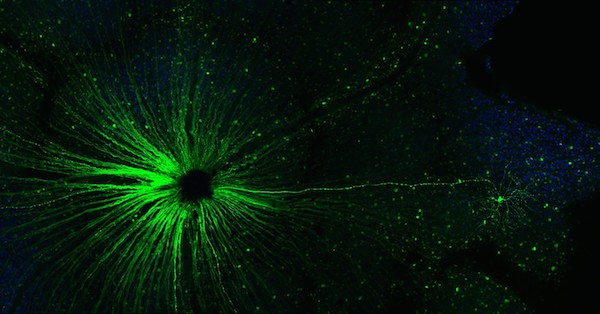

The LC is the main source of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine in the brain, and gets its name (Latin for “blue spot”) from the pigment neuromelanin, which is formed as a byproduct of the synthesis of norepinephrine and its related neurotransmitter dopamine. The LC has connections all over the brain, and is thought to be involved in arousal and attention, stress responses, learning and memory, and the sleep-wake cycle.

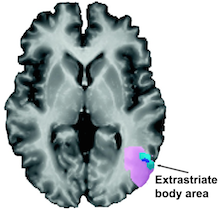

Cells in the locus coeruleus are lost in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s. From Kelly et al Acta Neuropath. Comm. (2017) via Creative Commons

The protein tau is one of the toxic proteins tied to Alzheimer’s, and it forms intracellular tangles. Pathologists have observed that precursors to tau tangles can be found in the LC in apparently healthy people before anywhere else in the brain, sometimes during the first few decades of life, Weinshenker writes. A similar bad actor in Parkinson’s, alpha-synuclein, can also be detected in the LC before other parts of the brain that are well known for damage in Parkinson’s, such as the dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra.

“The LC is the earliest site to show tau pathology in AD and one of the earliest (but not the earliest) site to show alpha-synuclein pathology in PD,” Weinshenker tells Lab Land. “The degeneration of the cells in both these diseases is more gradual. It probably starts in the terminals/fibers and eventually the cell bodies die.” Read more