To fight fat, scientists had to figure out how to pin down a greasy, slippery target. Researchers at Emory University and Baylor College of Medicine have identified compounds that potently activate LRH-1, a liver protein that regulates the metabolism of fat and sugar. These compounds have potential for treating diabetes, fatty liver disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

Their findings were recently published online in Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

LRH-1 is thought to sense metabolic state by binding a still-undetermined group of greasy molecules: lipids or phospholipids. It is a nuclear receptor, a type of protein that turns on genes in response to hormones or vitamins. The challenge scientists faced was in designing drugs that fit into the same slot occupied by the lipids.

“Phospholipids are typically big, greasy molecules that are hard to deliver as drugs, since they are quickly taken apart by the digestive system,” says Eric Ortlund, PhD, associate professor of biochemistry at Emory University School of Medicine. “We designed some substitutes that don’t fall apart, and they’re highly effective – 100 times more potent that what’s been found already.”

Previous attempts to design drugs that target LRH-1 ran into trouble because of the grease. Two very similar molecules might bind LRH-1 in opposite orientations. Ortlund’s lab worked with Emory chemist Nathan Jui, PhD and his colleagues to synthesize a large number of compounds, designing a “hook” that kept them in place. Based on previous structural studies, the hook could stop potential drugs from rotating around unpredictably. Read more

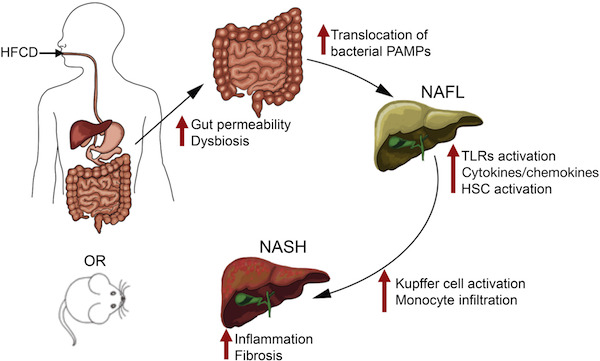

HFCD). This combination gives the mice moderate fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome (

HFCD). This combination gives the mice moderate fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome (