When doctors treat disease-causing bacteria with antibiotics, a few bacteria can survive even if they do not have a resistance gene that defends them from the antibiotic. These rare, slow-growing or hibernating cells are called “persisters.”

Microbiologists see understanding persistence as a key to fighting antibiotic resistance and possibly finding new antibiotics. Persistence appears to be regulated by constantly antagonistic pairs of proteins called toxin-antitoxins.

Basically, the toxin’s job is to slow down bacterial growth by interfering with protein production, and the antitoxin’s job is to restrain the toxin until stress triggers a retreat by the antitoxin. Some toxins chew up protein-encoding RNA messages docked at ribosomes, but there are a variety of mechanisms. The genomes of disease-causing bacteria are chock full of these battling odd couples, yet not much was known about how they work in the context of persistence.

Biochemist Christine Dunham reports that several laboratories recently published papers directly implicating toxin-antitoxin complexes in both persistence and biofilm formation. Her laboratory has been delving into how the parts of various toxin-antitoxin complexes interact.

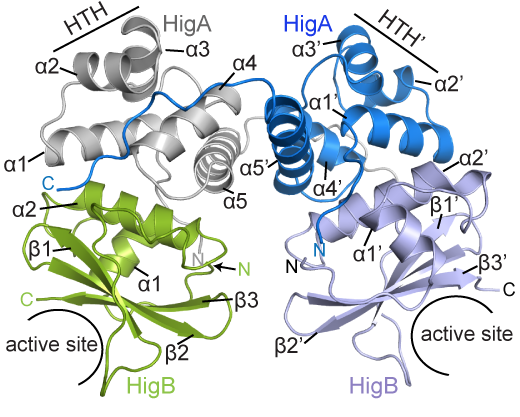

BCDB graduate student Marc Schureck and colleagues have determined the structure of a complex of HigBA toxin-antitoxin proteins from Proteus vulgaris bacteria via X-ray crystallography. The results were recently published in Journal of Biological Chemistry.

While Proteus vulgaris is known for causing urinary tract and wound infections, the HigBA toxin-antitoxin pair is also found in several other disease-causing bacteria such as V. cholera, P. aeruginosa, M. tuberculosis, S. pneumoniae etc.

“We have been directly comparing toxin-antitoxin systems in E. coli, Proteus and M. tuberculosis to see if there are commonalities and differences,” Dunham says.

The P. vulgaris HigBA structure is distinctive because the antitoxin HigA does not wrap around and mask the active site of HigB, which has been seen in other toxin-antitoxin systems. Still, HigA clings onto HigB in a way that prevents it from jamming itself into the ribosome.