Supported by a $8 million, five-year grant, an Emory-led team of scientists plans to investigate new therapeutic approaches to fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited intellectual disability and a major single-gene cause of autism.

Fragile X research represents a doorway to a better understanding of autism, and learning and memory. The field has made strides in recent years. Researchers have a good understanding of the functions of the FMR1 gene, which is silenced in fragile X syndrome.

Still, clinical trials based on that understanding have been unsuccessful, highlighting limitations of current mouse models. Researchers say the answer is to use “organoid” cultures that mimic the developing human brain.

The new grant continues support for the Emory Fragile X Center, first funded by the National Institutes of Health in 1997. The Center’s research program includes scientists from Emory as well as Stanford, New York University, Penn and the University of Southern California. The Emory Center will be one of three funded by the National Institutes of Health; the others are at Baylor College of Medicine and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

The co-directors for the Emory Fragile X Center are Peng Jin, PhD, chair of human genetics, and Stephen Warren, PhD, William Patterson Timmie professor and chair emeritus of human genetics. In the 1980s and 1990s, Warren led an international team that discovered the FMR1 gene and the mechanism of trinucleotide repeat expansion that silences the gene. This explained fragile X syndrome’s distinctive inheritance pattern, first identified by Emory geneticist Stephanie Sherman, PhD.

“Fragile X research is a consistent strength for Emory, stretching across several departments, based on groundbreaking work from Steve and Stephanie,” Jin says. “Now we have an opportunity to apply the knowledge we and our colleagues have gained to test the next generation of treatments.”

Looking ahead, a key element of the Center’s research will involve studying the human brain in “disease in a dish” models, says Gary Bassell, PhD, chair of cell biology. Nisha Raj, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Bassell’s lab, has been studying how FMR1 regulates localized protein synthesis at the brain’s synapses.

“What we’re learning is that there may be different RNA targets in human and mouse cells,” he says. “There’s a clear need to regroup and incorporate human cells into the research.”

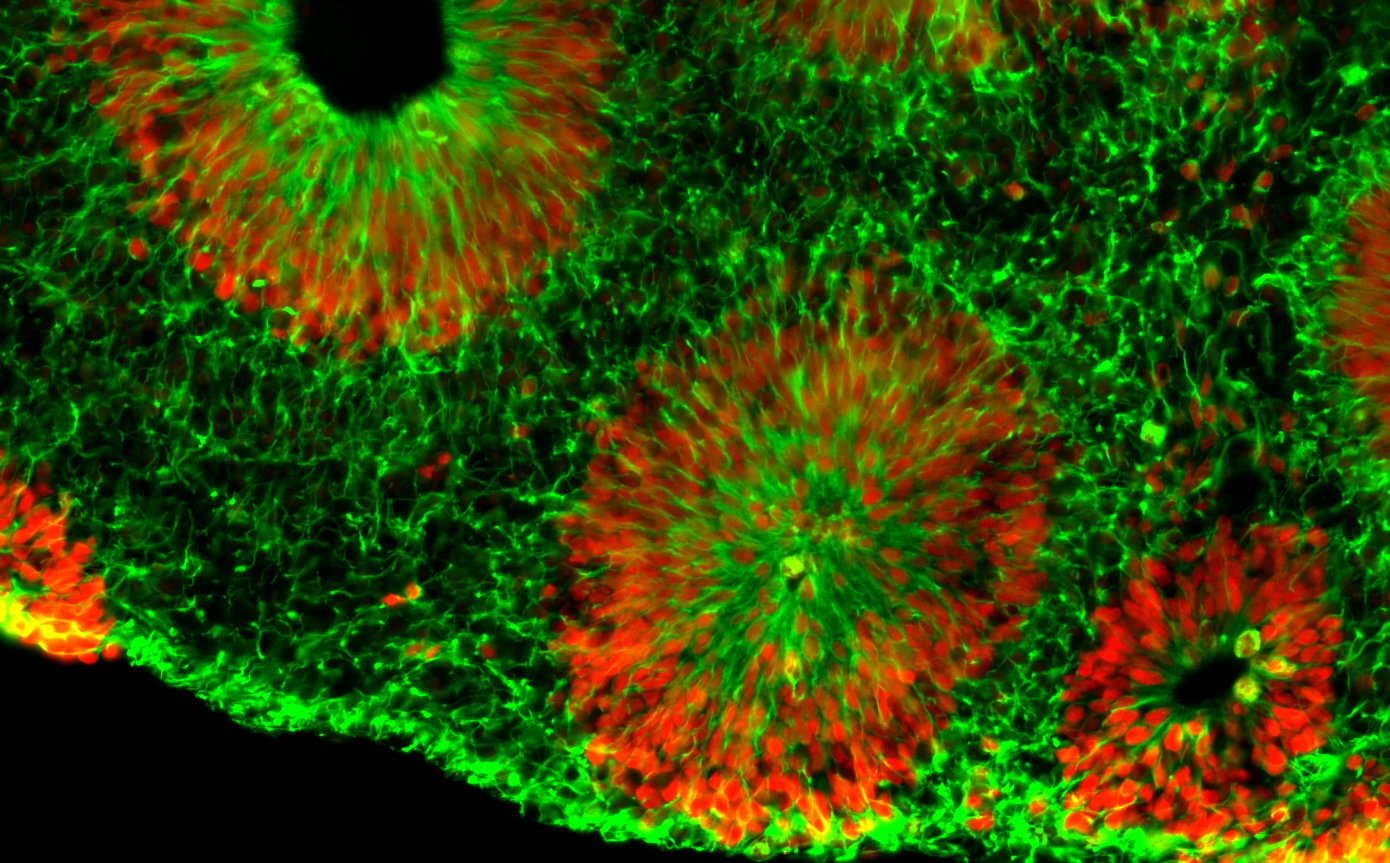

Center investigator Zhexing Wen, PhD, has developed techniques for culturing brain organoids (image above), which reproduce features of human brain development in miniature. Wen, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, cell biology and neurology at Emory, has used organoids to model other disorders, such as schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease.

The organoids are formed from human brain cells, coming from induced pluripotent stem cells, which are in turn derived from patient-donated tissues. Emory’s Laboratory of Translational Cell Biology, directed by Bassell, has developed several lines of induced pluripotent stem cells from fragile X syndrome patients.

“All of the investigators are sharing these valuable resources and collaborating on multiple projects,” Bassell says.

Principal investigators in the Emory Fragile X Center are Jin, Warren, Bassell, and Wen, along with Eric Klann, PhD at New York University, Lu Chen, PhD, and 2013 Nobel Prize winner Thomas Südhof, MD. Chen and Südhof are neuroscientists at Stanford.

Co-investigators include biostatistician Hao Wu, PhD and geneticist Emily Allen, PhD at Emory, neuroscientist Guo-li Ming, MD, PhD, at University of Pennsylvania, and biomedical engineer Dong Song, PhD, at University of Southern California.

Allen, Warren and Jin are part of an additional grant to Baylor, Emory and University of Michigan investigators, who are focusing on FXTAS (fragile X-associated tremor-ataxia syndrome) and FXPOI (fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency). These are conditions that affect people with fragile X premutations.

Fragile X syndrome is caused by a genetic duplication on the X chromosome, a “triplet repeat” in which a portion of the gene (CGG) gets repeated again and again. Fragile X syndrome affects about one child in 5,000, and is more common and more severe in boys. It often causes mild to moderate intellectual disabilities as well as behavioral and learning challenges. About a third of children affected have characteristics of autism, such as problems with eye contact, social anxiety, and delayed speech.

The award for the Emory Fragile X Center is administered by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.